With respect to the chaos at Chelsea, the struggles at Liverpool and the problems at Tottenham, there is no doubt about where the Premier League’s real crisis can be found these days.

What Everton fans would give to have those clubs’ issues right now. Struggling to qualify for the Champions League? Boo hoo! Not happy with your latest £60 million ($73m) left-back or your manager’s obsession with three at the back? The heart bleeds, it really does.

There are few English clubs as storied or as historic as Everton, but those who “know their history”, as the famous song goes, know that rarely has Goodison Park been as unhappy, or as toxic, as it is today.

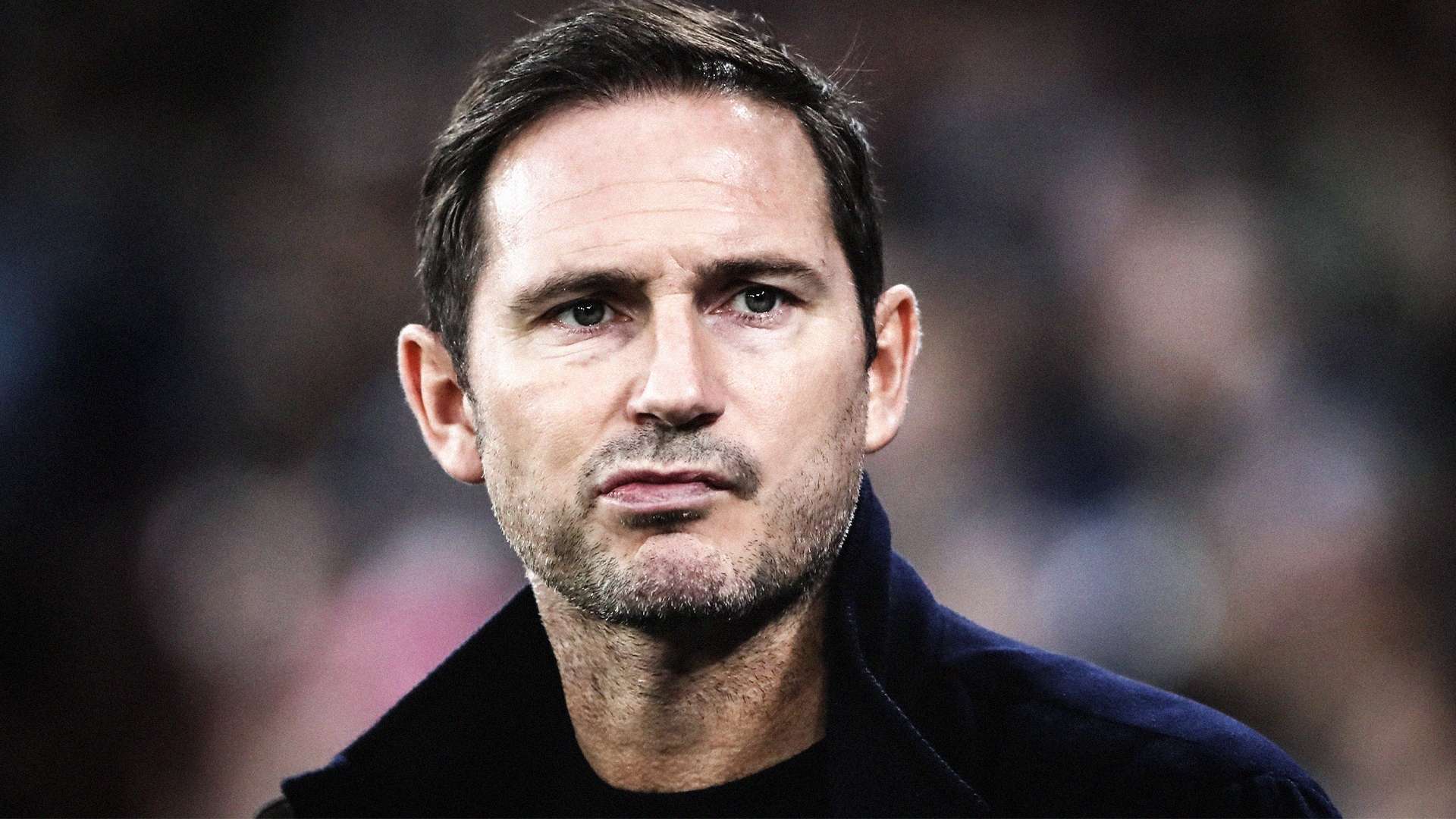

Saturday’s defeat to Southampton marked a new low, in that regard. Not only did it leave Frank Lampard’s side 19th in the Premier League and facing the prospect of a relegation battle for the second season running, but it also laid bare the complete, and quite staggering, breakdown in the relationship between the club and its long-suffering supporters.

The day started with the news that the Everton board – the chairman Bill Kenwright, chief executive Denise Barrett-Baxendale, finance director Grant Ingles and the non-executive director Graeme Sharp – would not be attending the game due to “a real and credible threat” to their safety and security.

A report in the Liverpool ECHO subsequently claimed that Barrett-Baxendale had been physically assaulted after the 4-1 defeat at Brighton on January 3, and that Kenwright had received death threats.

A sit-in protest was then held inside Goodison after the game, which Everton lost 2-1 having led at half-time, while outside the stadium players were confronted by angry supporters as they tried to leave in their cars.

Defender Yerry Mina was filmed speaking to fans in the street, while another video showed the vehicle of Anthony Gordon surrounded, as a chant of ‘You’re not fit to wear the shirt’ was directed at the home-grown winger.

Such ugly scenes, unsurprisingly, garnered national attention, although it should at this point be pointed out that the sit-in protest was conducted peacefully and that, on Monday, Merseyside Police issued a statement confirming that no threats or incidents involving Everton board members had been reported prior to the Southampton game.

Everton sources insist they did indeed take place, and that other staff members needed security escorts to their vehicles after the Southampton game, but the mere fact that their version of events is contested or doubted by supporters says plenty.

How did it come to this? Everton have been the sixth-biggest spenders in the Premier League since 2016, and will soon have a new 53,000-seater stadium on the banks of the River Mersey to call home, but they feel like a club which has not only stagnated, but moved significantly backwards under the stewardship of owner Farhad Moshiri.

That’s certainly the feeling of supporters. Earlier this month, 17 fan groups published an open letter to the British-Iranian businessman, urging him to make “sweeping changes at chair, board and executive levels” in order to “save the club from continued decline”. This week, the Everton Shareholders' Association launched an online petition calling for a vote of no confidence in the board. As of Friday evening, it had attracted almost 12,000 signatures.

Moshiri’s response has, it is fair to say, not gone down particularly well. In a letter addressed to the Everton Fans’ Forum, and published on the club’s official website, the 67-year-old reiterated his faith not only in Lampard and Kevin Thelwell, the director of football, but also in the board of directors.

“I am confident that we have skilled, experienced and focused professionals at all levels of the club,” he wrote.

A couple of days later came an interview with talkSPORT’s Jim White, in which Moshiri backed supporters’ “democratic right” to protest, but suggested that his ‘hire ‘em and fire ‘em’ approach to managers – Everton have had seven permanent bosses in seven years under his ownership – had been “driven by the fans, not me.”

Stability, he insisted, was key now, with the club going through significant changes.

The trouble is, it’s hard to have stability when relegation looms large, when your team is in decline and when there are no funds available to make it better.

Moshiri insisted to talkSPORT that he was an owner who “puts his money where his mouth is”, but Everton have squandered incredible amounts of it since he took charge, and are paying the price big time right now.

Getty

GettyThe list of failures is long and ugly, as a series of managers, and no fewer than three directors of football, have sought to bring in their own players, leaving Lampard and Thelwell, who are both less than 12 months into the job, with what one source has described as “a box containing pieces from four different jigsaws".

Everton’s current squad contains players signed under David Moyes, Roberto Martinez, Ronald Koeman, Marco Silva, Carlo Ancelotti, Rafa Benitez and Lampard.

They have the likes of Dele Alli, Moise Kean, Andre Gomes and Jean-Philippe Gbamin out on loan, and have been forced, in recent windows, to accept huge losses on signings such as James Rodriguez, Allan, Fabian Delph, Cenk Tosun, Yannick Bolasie, Theo Walcott, Oumar Niasse, Sandro Ramirez, Morgan Schneiderlin, Wayne Rooney and Davy Klaassen – most if not all of whom failed to make any kind of lasting impression in their time at the club.

Moshiri arrived in 2016 promising to transform the club’s fortunes, but his spending has been so reckless, and the returns so slim, that Everton are now paying an even heavier price.

Their most recent accounts, published last March, saw them post losses of more than £120 million ($148m), and their total losses over a three-year period stand at over £370m ($456m) – well above the Premier League's financial fair play threshold, and bringing about genuine concern as to how much longer the club can continue to hold back the tide.

The situation was so stark last summer that Richarlison, the club’s best and most valuable player, was sold to Tottenham in order to ensure compliance with financial fair play rules.

The money received, around £60m ($74m) then had to be used to somehow strengthen five or six different areas of a squad which had, even with the Brazilian international, only narrowly avoided relegation last season.

Unsurprisingly, it hasn’t worked. In fact, Everton look weaker now than they did 12 months ago.

They have won only three of their first 19 games, are out of both domestic cup competitions and are currently on a run of one win in 13 matches in all competitions. They have scored only 15 league goals, the joint second-lowest total in the league, and they look, and feel, like a side heading for the Championship.

Defeat this weekend at West Ham, the side directly above them in the table, would surely spell the end for Lampard.

Moshiri insists that “rash decisions” are not needed, but his modus operandi has been to pull the trigger when things reach a certain point, and the feeling is that he will revert to type sooner rather than later.

He did so with Benitez a year ago, when the Blues were 15th, and he did the same with both Koeman and Silva mid-season, despite both being heralded as long-term solutions when appointed.

Lampard, who has the lowest win percentage of any Everton manager since Howard Kendall in 1997-98, could have few complaints if he were sacked, even if he retains a certain level of support and sympathy from supporters.

The majority, at least, are aware that this is a club which needs far, far more than a change of manager.

.jpg?format=pjpg&quality=60&auto=webp&width=380) Getty

GettyEverton’s last two before Lampard – Benitez and Ancelotti – are Champions League winners. Silva’s ability is there for all to see in his work with Fulham. Koeman and Martinez are managing big players at international level, while Allardyce, although an unpopular appointment, has a fine record in the Premier League and was good enough to be appointed by England once upon a time.

As one source told GOAL: “they can’t all be wrong, can they?”

Changes have been implemented at the club, in particular in terms of the academy and in departments such as analysis, sports science and physical conditioning.

Thelwell, the former Wolves and New York Red Bulls sporting director, has made 26 appointments since his own arrival last February, bringing experienced and specialist personnel, and there is hope that the mistakes of the past, in particular the money spent on players with little-to-no resale value, will not be repeated, with the scouting and recruitment strategy a lot clearer and a lot more connected.

Signings such as Amadou Onana (21), James Garner (21) and Dwight McNeil (23) hint at the new policy, to sign young players with potential and sell-on value, although Everton’s financial constraints have meant that short-term signings such as Conor Coady, Ruben Vinagre and Idrissa Gueye have also been deemed necessary.

Thelwell and Lampard would like to bring two, ideally three, attacking players in before the January window shuts, but they are likely to be loan deals, with Manchester United’s Anthony Elanga, Villarreal’s Arnaut Danjuma and Rennes’ Kamaldeen Sulemana among those in the frame. A deal for Danjuma looks likely.

What a contrast with Saturday’s opponents. Unlike Everton, West Ham have been able to recruit ambitiously in recent windows, spending more than £160m ($195m) on the likes of Gianluca Scamacca, Lucas Paqueta and Maxwel Cornet (a player Everton targeted) in the summer, and adding Danny Ings, another played coveted by the Blues, this week.

They have a strong squad, good players and European football to look forward to in 2023.

Yet the Hammers still find themselves only one place and one goal better off than Everton, without a league win since October and with their manager, David Moyes, under as much pressure as Lampard. Moyes will, according to reports this week, be sacked if his side lose on Saturday, and it would not be a huge surprise if he were on Everton's radar, if and when Lampard goes.

This is then, without doubt, the biggest game of the Premier League weekend. A relegation six-pointer, if ever there was one.

For Everton, though, even a win will not be enough to soothe fans’ concerns. They will make themselves heard at West Ham, of course. They always do.

It was their support, and the impact that had, which helped keep the club afloat last season, when at one point they looked doomed, and if they are to haul themselves away from danger again this time around, then a similar effort will be required. Goodison needs to roar, louder than ever before.

And doesn’t that just tell you everything? This is a club which was dreaming of the big time not so long ago, but which through poor decisions, rotten communication and wasted money, has managed only to paint itself into a corner, without a plan and without a clue, needing its long-suffering fans to help bail them out.

Once again, relegation looms large, and this time the team – and the club – looks far less well-equipped to avoid it. The next few months are among the most important in Everton’s 145-year history.