The Champions League final, last May.

A heart-breaking night for those of a Liverpool persuasion. An evening defined by Mohamed Salah’s injury, Gareth Bale’s brilliance and Loris Karius’ anguish. A tearful conclusion to a remarkable journey.

For some, Kiev was the end of that journey. For Mike Gordon, Jurgen Klopp and his staff, however, it was merely a stop-off point.

Indeed, even as the Reds took to the field against Real Madrid, plans for the next stage of their development were already being finalised. Standing still, Liverpool have grown to realise, is never an option.

The night before the final, on the rooftop terrace of the Intercontinental hotel, a familiar face had mingled with Klopp and his players.

Pep Lijnders had left the Reds’ backroom team that January, taking on his first senior managerial role with NEC Nijmegen in the Netherlands, but here he was, back in the picture; smiling, debating, encouraging. Part of the group again.

Preparing, as it turned out, to return to Liverpool that summer.

“I had already spoken about it when I went to Kiev,” Lijnders reveals, almost nine months on. “I already knew the ideas from Jurgen, so it felt good to be there the night before, with the staff and with Jurgen and the boys. I knew I was going to be coming back at that point.”

Lijnders’ return was instigated by Klopp and by Mike Gordon, Liverpool’s co-owner. His time at NEC had ultimately ended in failure – missing out on promotion to the Eredivisie through the play-offs – but at Anfield his reputation could not be better.

The Dutchman – hands-on, sharp and almost obsessively passionate about his work – is seen as one of the outstanding coaches in Europe.

With Zeljko Buvac, Klopp’s long-time assistant, having suddenly departed the club in April, Lijnders would return in a more senior role than the one he had vacated. He would essentially, along with Peter Krawietz, become Klopp’s new right-hand man.

Getty

GettyHe would also take on the vital role of leading the next phase of the Reds’ tactical evolution.

That involved implementing a more controlled, patient, style of play. “Organised chaos,” is a term used at Melwood to describe Klopp’s philosophy, but the chaos has not always been matched by the organisation.

Liverpool, for example, scored 47 goals in just 15 Champions League games last season, with their front three alone managing 91 in all competitions. Yet they finished the season trophy-less, squeezing into fourth place in the Premier League ahead of Chelsea on the final day.

To go from ‘good’ to ‘great’, Klopp reasoned, they needed to modify their approach, become a more controlled, streetwise team.

“Jurgen was very clear what the next step would be,” Lijnders says. “We spoke a lot before I took the job, and one thing we were both really agreeing on was how our midfield play could improve.

“[It was important] that we could create a free player more easily, that we could find him in an easier way. From there, we would have better movements in there to attack their last line. But especially that midfield play [had to improve].”

The solution lay not only on the training field, but in the transfer market.

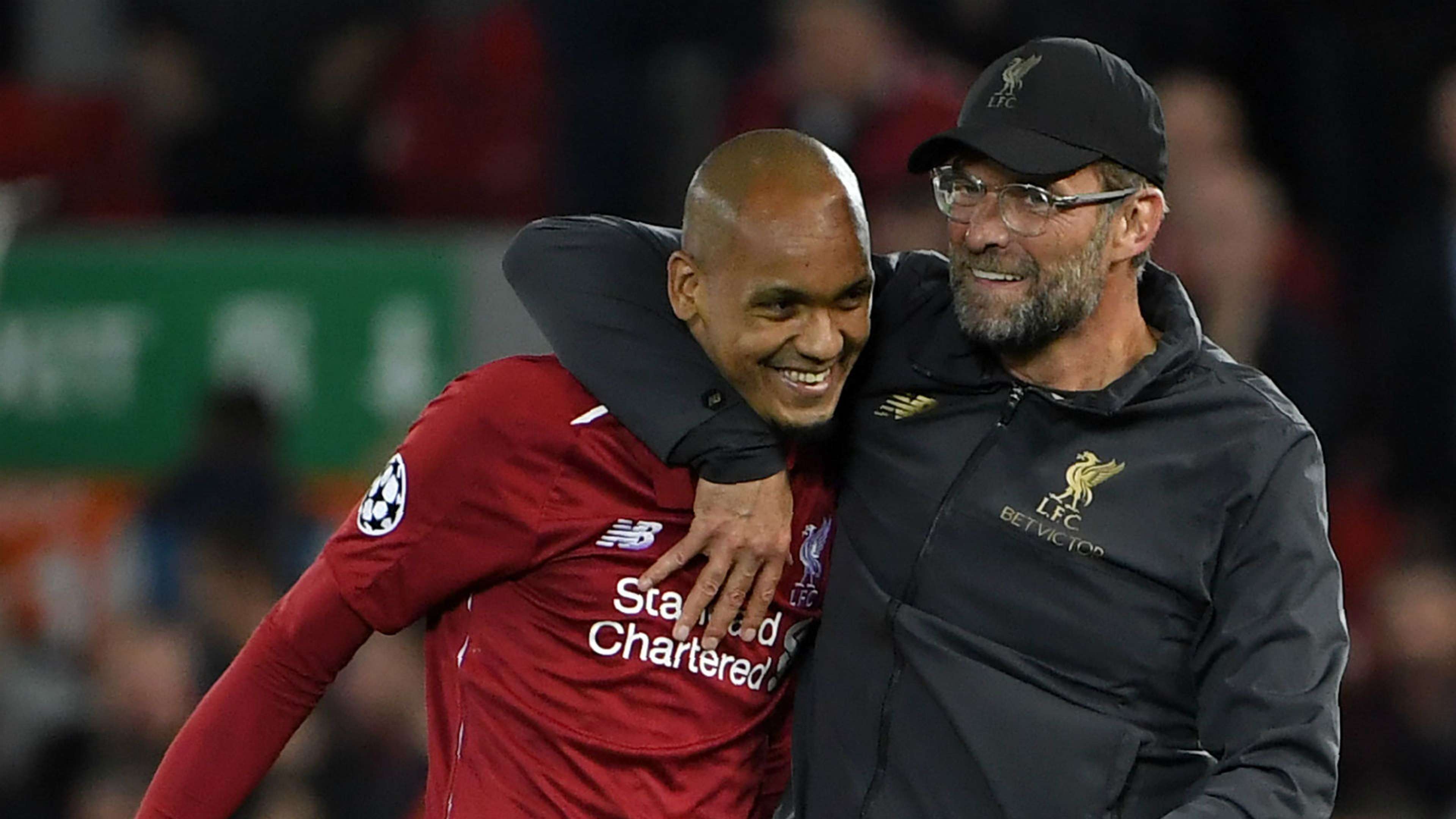

Less than 48 hours after the Champions League final, Fabinho was recruited from Monaco to bolster Klopp’s midfield options. With Naby Keita arriving from RB Leipzig on July 1, Liverpool had spent more than £90 million ($115m) on improving one of their target areas.

Still, it would take time. Fabinho’s settling-in period was tough; he didn’t start a league game until October and was often not even part of the matchday squad. Training was tough, and questions were asked.

Lijnders, a fluent Portuguese speaker, played a big role in ensuring the Brazilian remained focused and patient.

“To adapt to the intensity of our play, that takes time,” he says. “Not many can do it, and in certain positions it is easier than others.

"If you are a front player and you come in, and you are used to playing in an attacking way, then it is easier, depending on the specific attributes you have as a player.

“For Fabinho, to play in a midfield three as we did at the start of the season, we knew it would take time. His impulse of defending forward is absolutely of the highest level, elite. The question as a No.6, though, is that you are moving more side-to-side than forwards.

“Then, of course, you have to adapt to the league and the team. We found a good solution to change to 4-4-2 (4-2-3-1). And from that moment it helped so much, and then you saw the real Fabinho.”

His improvement since has been striking, whether as part of a ‘double six’ or in the more familiar 4-3-3 formation. He’s even, of course, filled in admirably at centre-back, and may be required to do so against Bayern Munich next week.

“Inside the ‘organised chaos’ that we want, that we like, he is like a lighthouse,” says Lijnders. “He controls it.

“There’s a saying in Portuguese, ‘A bola sempre sai rodada’. It means ‘The ball always goes out round’ and with a player like Fabinho in the middle, you can see that.

"His timing, his vision, his calmness, it gives another dimension to our midfield play.”

Alongside him, or sometimes in front of him, the form of Gini Wijnaldum, Lijnders’ fellow Dutchman, has been equally impressive.

“I would say that Gini and Bobby [Firmino] represent ‘our way’ in the best way possible,” Lijnders says, puffing his cheeks out. “Because we want players who are responsible for everything.

“Gini is a player who can drop and create three at the back for a short period of time, bring the ball out, and at the same time turn in midfield and find somebody straight away in between the lines.

"And then he can pass and move into the last line or even over the last line. He can arrive in scoring areas, he can head, he can score.

“He’s also still learning. Football is a game where you never stop learning and he’s becoming a better player. I think he represents what we want in a player, really well.”

Firmino, meanwhile, has seen his role evolve too, often finding himself as a roving No.10 in the 4-2-3-1 system, with Mohamed Salah used as the No.9.

It was a bold move, given Salah’s 44 goals from a predominantly right-sided station last season. But with the Egyptian having passed 20 for the campaign last weekend, and with the team continuing to perform, the results are there to see.

“First of all, Mo has the ability to create from the inside,” says Lijnders, explaining the change. “That differentiates him from many others of his type. He’s a real goalscorer.

“So, to have him in the last line as high as we can, with the speed he has, the goal threat he has, it makes it easier for us to create a freer role for Bobby.

“For Mo, it's really good to understand the game in that way, to be the point. For him it's great. He's closer to the goal, he can use his speed more, he's more where we want him to be. That's a natural development for him.”

Getty

GettyStill, was it not an issue to tell Salah, with his array of personal awards and his rising global profile, to change his role?

“No,” Lijnders replies. “I think how this team is constructed anyway, it's glued by character, ambition and passion. It really fits well.

“That's what I say has influenced the evolution. You bring in not only world-class players, but players who are very hungry for training as well. That's what I like most about our project.

“If you look to our squad and what we are trying to achieve and what we are achieving, that hunger for becoming better is clear.

“Mo is a good example of that. He's always searching for the next step and the next level. For me, the difference between a good player and a top player is that the top players can solve problems before they become problems, or they can solve problems in many different ways. And a top player can do it constantly. Mo does that.”

He certainly does, and as Liverpool head into the final third of the season, they find themselves well and truly alive in the two competitions they crave most.

The Premier League title race threatens to go down to the wire, while the Bayern tie should ensure another pair of classic Champions League nights.

“These moments made the team smell the hunger for the last step,” says Lijnders, with a smile. “With all we did so far, we are trying to make this last step.”