Socrates could have played in the 1978 World Cup. He was 24 years old at the time, but was unable to participate because he was pursuing his medical studies. 'Doctor Socrates' therefore only made his debut for the national team a year later. By then, he was already playing for Corinthians, which was soon to become one of the most exciting football projects in the world.

After sporting failures under an authoritarian club management, Waldemar Pires was elected the new president in early 1982, and he subsequently appointed the sociologist Adilson Monteiro Alves as sporting director. Together, they gave their players complete creative freedom.

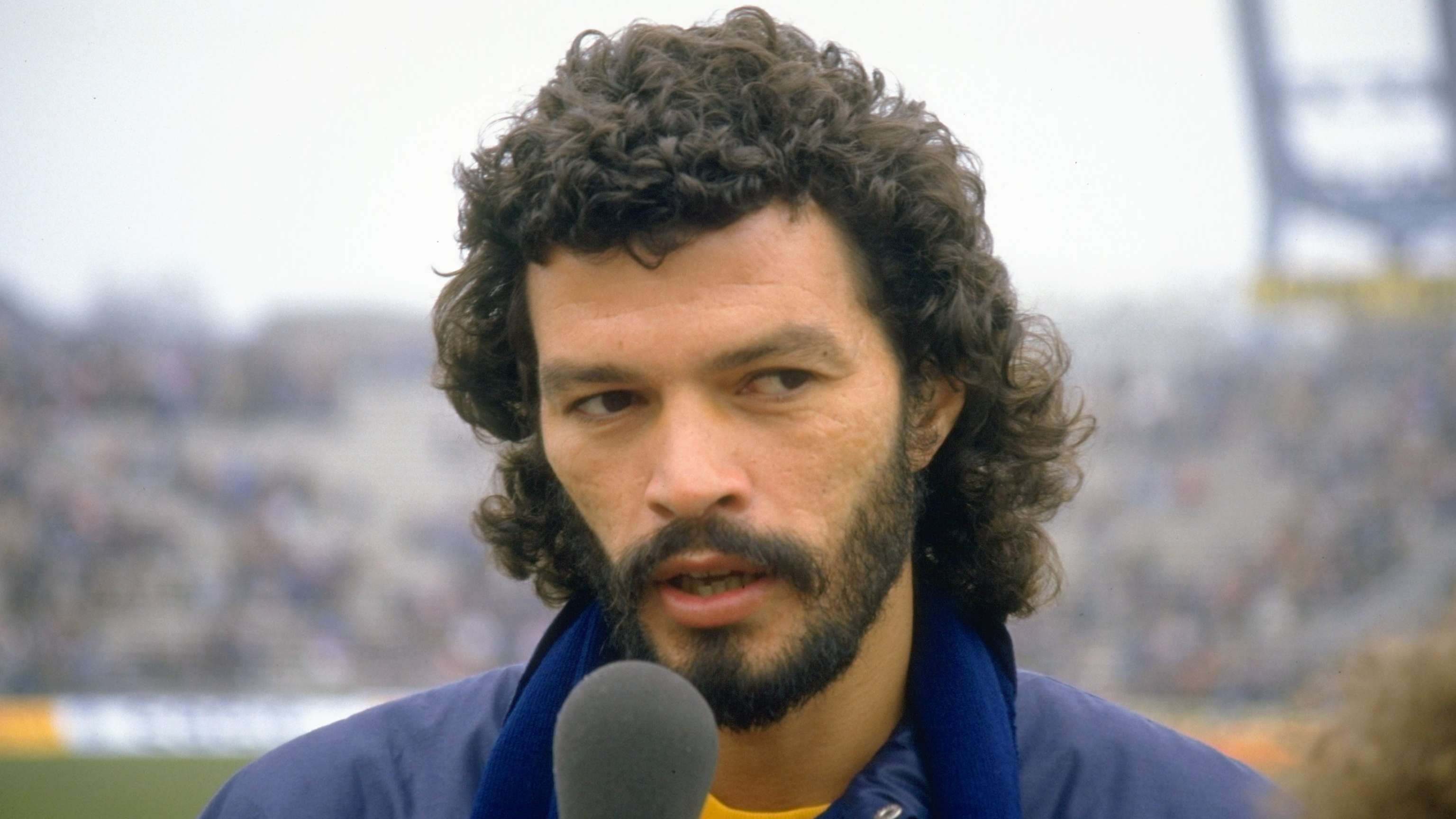

At the time, Corinthians had a number of politically active players. Wladimir, who not only defended on the left side of the pitch but also the political spectrum; Walter Casagrande, whose political activities even landed him in prison for a short time; and above all Socrates, whose head resembled Guevara both inside and out. "I would like to be Cuban," he once said.

Socrates and his comrades created grassroots democratic structures at Corinthians. Players, coaches and officials voted by majority decision on all decisions, no matter how minor. Every opinion was sought for matters from new signings, sales, sackings and line-ups to training times and the canteen menu. At the same time, the rules of the so-called Concentracao, where players were locked in a hotel before matches, were relaxed.

The concept was dubbed 'Democracia Corinthiana'. However, this unique football club was not only concerned with internal matters, but also with the state of the nation. On their jerseys, Corinthians criticised the military dictatorship that had ruled Brazil since 1964 with slogans such as "Direct elections now" and "I want to elect the president". Socrates himself liked to wear white headbands with special messages: "People need justice," "Yes to love, no to terror," and "No violence".