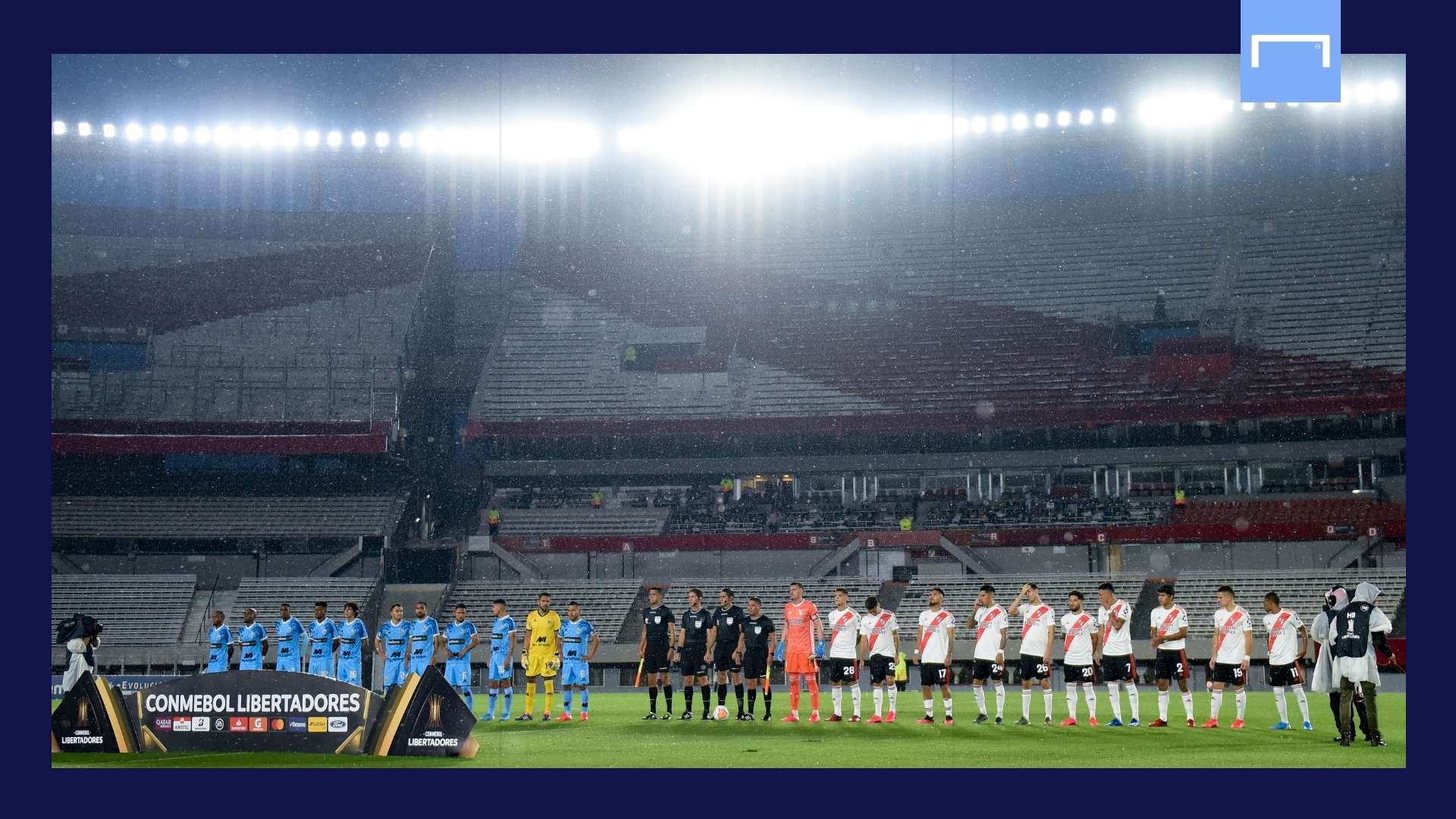

Under normal circumstances, a Tuesday afternoon kick-off in Asuncion between River Plate and Nacional would invite little interest from anyone not directly connected to the two clubs.

But the 1-1 draw between River and their rivals from the Paraguayan capital marked a breakthrough in South America: the first national league game played anywhere on the continent for the best part of four months.

While the coronavirus pandemic first caused devastation in China and later the likes of Italy, Spain, Great Britain and the United States, its effects have also been felt keenly, if unevenly, in the Southern Hemisphere.

All 10 members of CONMEBOL suspended their league competitions in March, but recovery in a region where indicators such as healthcare and infrastructure, poverty levels, informal labour practices and states' efficiency all work against a coordinated response to such a catastrophe has been slow, frustrating work, made even more difficult by the refusal of certain governments to take Covid-19 seriously.

Brazil, for instance, was the first nation to sanction a restart, in its state championships, even while the number of confirmed cases and deaths continued to rise in an alarming manner. As of Friday 56,000 new infections were confirmed for a total of 2.3 million, a figure behind only the United States globally, while on the same day 1,156 people passed away to bring the number of fatalities to more than 85,000 since the start of the pandemic.

But while President Jair Bolsonaro's incompetence and aggressive denial of coronavirus' severity has made Brazil headline news, it is far from being the only country stricken in South America. Peru and Chile also feature in the world's top 10 for total cases, while no other nation on the planet has suffered more cases per capita than the latter.

All three nevertheless voted to resume the flagship Copa Libertadores competition in September, as did Ecuador – where seemingly low Covid-19 figures have been placed under huge scrutiny following the images of mass graves and collapsed hospitals that have emanated from the country since March.

Indeed, of CONMEBOL's member nations, only two voted against the Copa's return. Argentina initially recorded a laudable reaction to the unveiling disaster, with strict nationwide quarantine regulations slowing the rate of infections and allowing for investment in ailing health facilities, albeit at a harrowing economic cost.

Getty/Goal

Getty/Goal

Those measures have largely eradicated the virus in most of the nation; but in the Greater Buenos Aires area, a conglomeration of over 15 million, cases continue to rise amid rising discontent and resistance to lockdown, leaving football as an afterthought for those in charge.

The tragedy has hit even harder in Bolivia, who with its neighbour registered lonely opposition to the plan. De facto head of state Jeanine Anez returned a positive Covid-19 test as did FA chief Cesar Salinas; on Sunday, the 59-year-old passed away, sending the country's football community into mourning.

Whether one wishes to focus on Bolivia, where in five days more than 400 bodies were removed from the streets and homes, Colombia, with over 200,000 cases and 7,000 deaths, or Venezuela, where the very statistics are contested and President Nicolas Maduro pins responsibility on mafias and rabble-rousers sent in from Colombia, the panorama is bleak. Even once the pandemic finally ends, South America faces a humanitarian catastrophe: 29 million inhabitants, equivalent to the entire population of Venezuela, who have fallen below the poverty line as a result of the events of the past six months, according to estimations given by Action Against Hunger in Latin America.

Only Paraguay and Uruguay – by far the smallest states in terms of population in South America – can claim to be turning the corner, and even the former was forced to push back football's original return date due to a spate of new infections inside clubs. In a farcical twist, the entire playing squad of 12 de Octubre tested positive last Friday and, to a man, returned negative results five days later to resume training.

In such a nightmarish context even thinking about the resumption of sporting activities can easily seem frivolous.

Getty/Goal

Upon taking the field for the first time in the Paulista Championship on Wednesday, Brazilian giants Corinthians held up a banner stating “The People's team mourns the victims of Covid.”

Getty/Goal

Upon taking the field for the first time in the Paulista Championship on Wednesday, Brazilian giants Corinthians held up a banner stating “The People's team mourns the victims of Covid.”

On the same day, Bahia took the field with their club badge partially covered by a surgical mask and with a message of support to beleaguered medical workers on their shirt, while weeks earlier in Rio de Janeiro rivals Fluminense and Botafogo came together in a similar message of protest before their Carioca clash, calling on authorities to “Respect our history” after first threatening to take their wish not to play to the courts in clear defiance of Bolsonaro.

Some, on the other hand, believe that those in charge have not moved quickly enough to restore normality.

“With the league [the Argentine FA] has made rash decisions,” River Plate coach Marcelo Gallardo fired back in June, frustrated at the lack of movement in resuming training sessions. “From there they said, 'let's see what happens'. What do you mean, 'see what happens'?

“I see an Argentine football which is clearly going into decay. I am really worried about where Argentine football is going.”

The case of San Martin de Tucuman is an eloquent example of the damage caused these past months. The club sat atop Argentina's second-tier Primera Nacional in March when the pandemic hit, but saw their petition to gain promotion upon the suspension of the league fall on deaf ears at the AFA.

The Ciruja will have to play an as of yet unconfirmed play-off competition to go up; but in the meantime their bank balance has been ravaged and the club, running on a deficit of $20 million (£220,000/US$280,000), has been forced to release all but five players to pay the bills.

“The AFA did more damage than coronavirus,” president Roberto Sagra fired to Ole on Monday, while he waits for the Court of Arbitration for Sport to rule on San Martin's case against their own association (“Even if they rule in favour, I don't know whether this club can recover”).

In Bolivia, meanwhile, Primera Division side Blooming's squad have threatened strike action over unpaid wages, having failed to receive a single pay cheque in the four months since the league was halted.

Goal

Goal

These are not Bundesliga, La Liga or Premier League millionaires holding struggling clubs to ransom, but professionals who depend on their modest incomes – the average monthly wage is around US$4,000, with many earning less than half that sum – to support themselves and loved ones.

“You put yourself in the club's shoes and we see there is no income, it's been four months without football, but we also have families and need to be paid,” Blooming's Helmuth Gutierrez explained.

“We have been understanding because the pandemic hit everything and affected the entire world, but four months have now passed since we last got paid and we cannot go on like this.”

At least some sort of normality will be regained in the coming months, with Paraguay under way, Chile, Uruguay and Brazil aiming for the start of August to launch their own leagues and Argentina planning a condensed version of the top flight to coincide with the start of the Copa a month later.

But even in this most optimistic scenario, the outcome of coronavirus on football will be hundreds of clubs either bankrupt or on the brink of extinction, thousands of players and club employees unpaid and out of work and stadiums robbed of the passion and colour which makes the South American game so fascinating in the first place.

It will take the region's countries months, if not years, to recover from the shattering effects of the pandemic, and things will likely never be the same again for vast swathes of the population.

To think football would be immune to such upheaval is naive in the extreme: the outlook is bleak whichever way one looks at it, with the promise of more pain and upheaval to come before a full recovery can even be contemplated.