On November 17, 1993, French football collapsed. At Parc des Princes, Emil Kostadinov's killer goal in the dying seconds for Bulgaria didn't just deny France a place at the 1994 World Cup, it plunged an entire nation into sporting mourning amid collective shame.

The national team was a smouldering ruin, a divided and broken squad, and the betrayed public wrapped itself in icy mistrust. Manager Gerard Houllier resigned, leaving his assistant, Aime Jacquet, to inherit the wreckage. Appointed on an interim basis, Jacquet was perceived as a mere caretaker, an austere man tasked with managing an inglorious transition. France, due to host the 1998 World Cup, seemed condemned to play second fiddle on home soil.

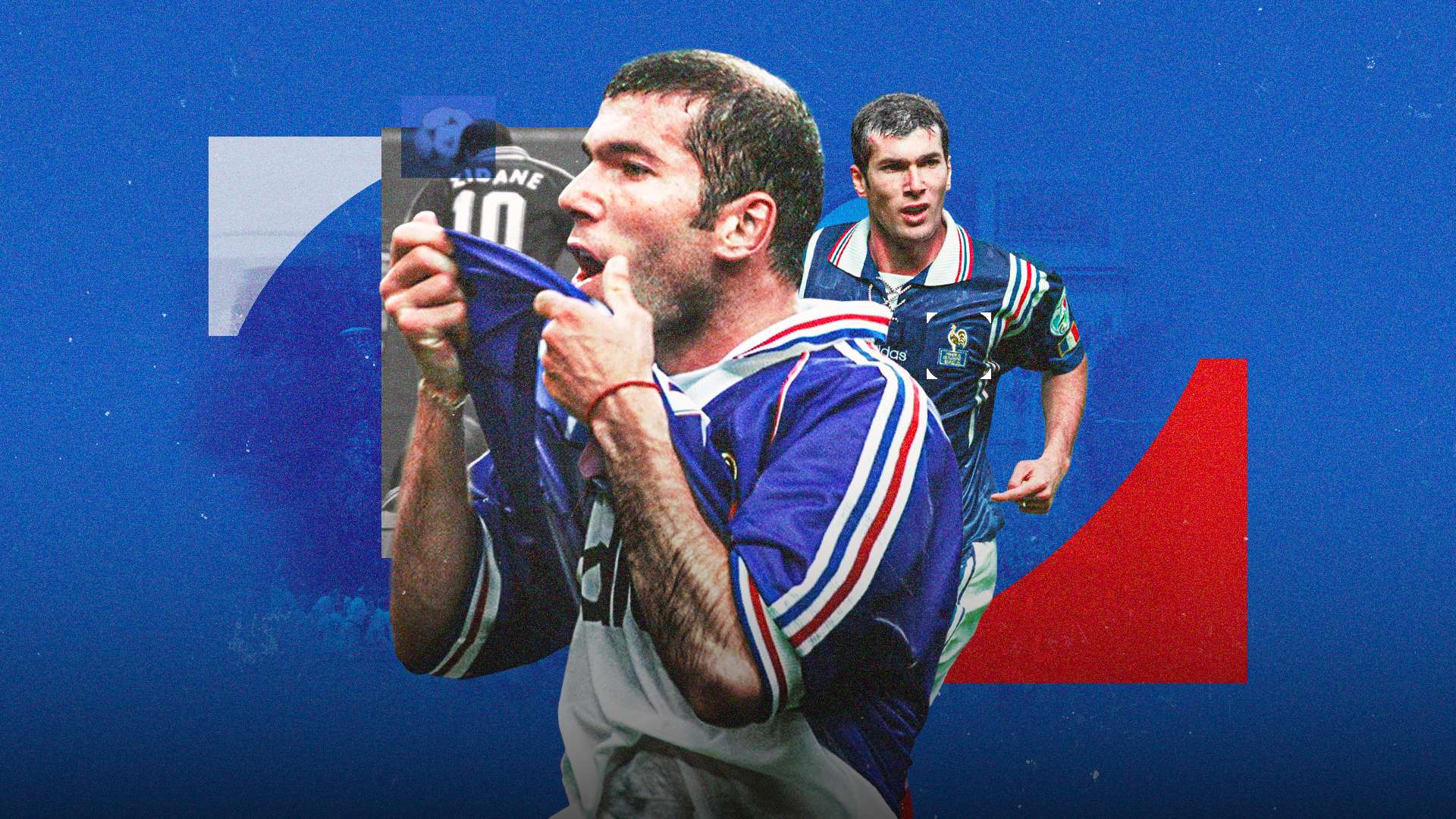

Then, nine months later, on August 17, 1994, a light pierced the darkness. In Bordeaux, with France trailing 2-0 to the Czech Republic, a 22-year-old playmaker named Zinedine Zidane entered for his first cap. Within a few surreal minutes, he had scored two sumptuous goals and salvaged a draw.

It was a flash of pure genius, an unexpected miracle that seemed to herald rebirth for the team, and yet this stunning debut wouldn't mark the arrival of an immediate superstar, but was instead the first act of a four-year odyssey that proved to be winding and riddled with doubt. How did this shy prodigy from the northern districts of Marseille navigate outsized expectations, caustic criticism and his own demons to become the undisputed leader and eternal hero of 1998?