World Cups are usually marked by uncertainty - their unpredictability is what makes them so compelling. But the 2026 edition will arrive loaded with certainties. For the Brazilian national team, it will be a turning point in history: either Carlo Ancelotti’s men earn their long-awaited sixth star, or they will set a record for the longest title drought Brazil has ever endured.

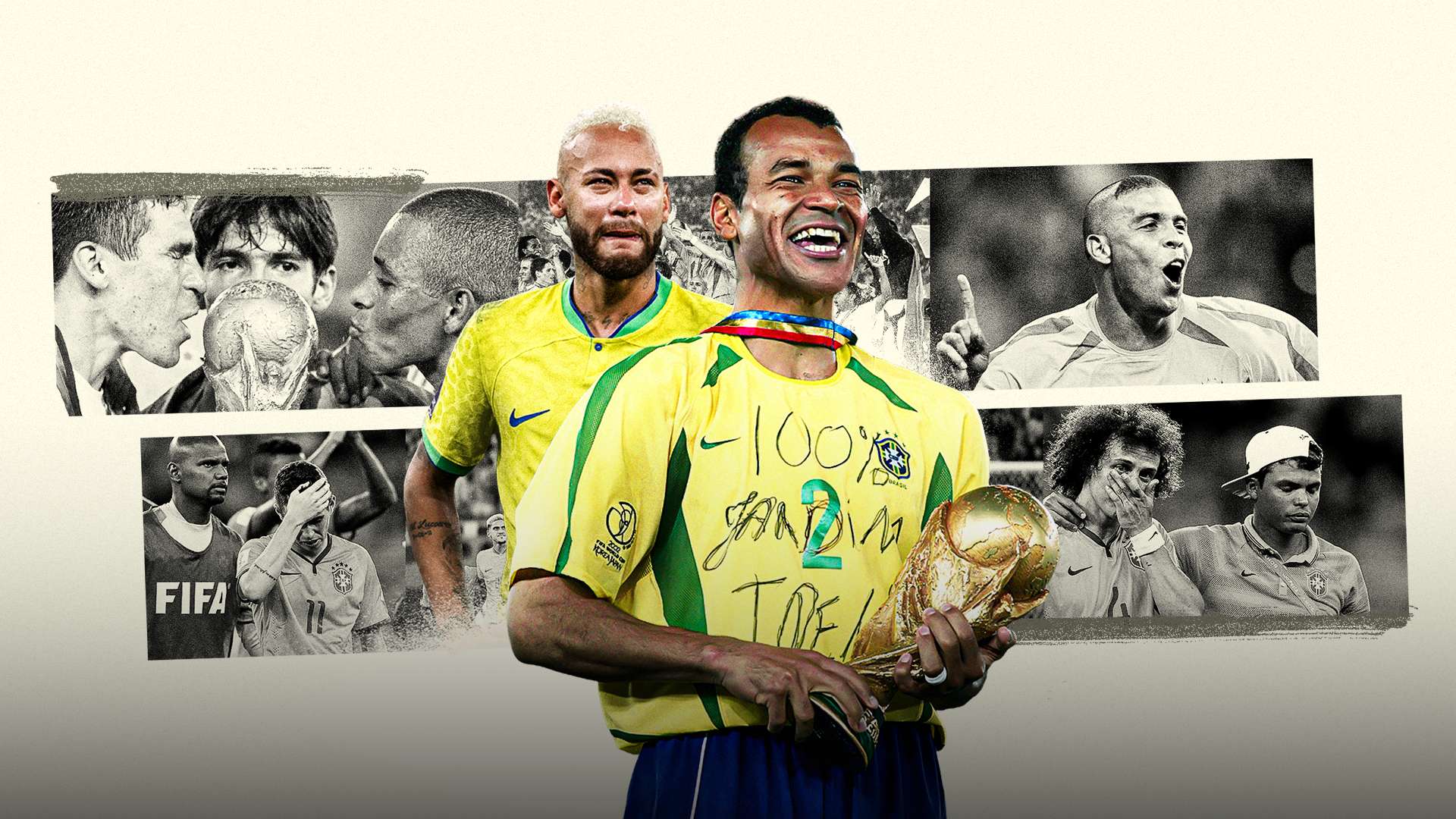

It’s been 24 years since Brazil’s last triumph in 2002 - the same gap that separated the 1970 title, won by the all-star team that featured Pele, Jairzinho, Gerson, Rivellino, Tostao and company, from the triumph in 1994. Five straight tournaments without the Selecao lifting the trophy. The math is simple: if the drought doesn’t end next year in North America - as it did on that sunny afternoon at the Rose Bowl, when Roberto Baggio sent his penalty kick flying over the bar - then the wait will stretch to 28 years and six World Cups by 2030.

Brazil has never waited this long for a global title. The first edition of the tournament was in 1930, and while Brazil’s first trophy came 28 years later, in 1958, the country only realistically began dreaming of lifting the trophy in 1950, when it hosted the tournament for the first time. Just eight years separated the scene of a young Pele comforting his tearful father after hearing the ‘Maracanazo’ on the radio from him crying tears of joy, embraced by Nilton Santos, following Brazil’s victory over Sweden in 1958.

From that first title onward, Brazil became synonymous with beautiful soccer, with passing, dribbling, goals, artistry. The yellow jersey became the most recognised and revered sports symbol on Earth. The ‘country of football’, the ‘Jogo Bonito’. The second title followed quickly, in 1962, and the disappointment of 1966 lasted only four years before the 1970 team - televised globally for the first time - sealed Brazil’s place as kings of soccer and Pele’s as the greatest player of all time.