For a moment, Robbie Fowler is transported back to his playing days.

The sights and the smells, the feelings, the excitement, the nerves, the tension, the noise.

Or rather, THE noise. The only noise that mattered, anyway.

“Do you know what the best sound in football is?” the Liverpool legend asks Goal, his voice dripping with nostalgia.

“It’s the noise when the ball hits the back of the net. That sound, it’s just sheer satisfaction. That’s what I lived for. I absolutely love it.”

Fowler, of course, has enjoyed that sound more than most over the years. Few players can match his hunger for goalscoring. Even now, 45 years old and the manager of Australian A-League side Brisbane Roar, the urges are still there.

“I can barely walk now, let alone run!” he says. “But if I see a ball lying around, I can’t help myself. I have to smash it into the goal, I just have to. I need it. I need that sound.”

Fowler’s passion almost jumps down the line as we enter into a discussion on the art of goalscoring. He may be forging a successful career as a manager, but this is his specialist subject; the No.9, the predator, that never-ending desire to be the hero.

“That’s what I wanted – to be the hero,” he says. “It was always the buzz for me. It was why I wanted to play.

“I talk about the sound of the ball hitting the back of the net, that can be on the park or on the training field or in the back garden, but when it’s in a proper game and you see the goalkeeper scrambling across, trying to get there, and you know he can’t. That’s as good as it gets.”

You’ll all know Fowler’s MO by now, surely? He was the Toxteth Terror, the man who, to use a wonderful phrase from The Guardian’s Rob Smyth, “fused the mischief of Ferris Bueller with the swagger of Liam Gallagher”.

Liverpool fans call him ‘God’, and with good reason. Fowler sits sixth on the club’s all-time goalscoring list and seventh on the all-time Premier League chart. Had it not been for the injuries which blighted the second half of his career – and which mean he struggles to run now – his numbers would have been even more impressive.

Speak to those who saw him, or to those who played with him, and most would say the same. “A natural goalscorer,” they’ll tell you, someone who just had “the knack” for scoring goals, things you couldn’t teach, couldn’t coach.

How does Fowler himself see it?

“You know, it used to be a bugbear of mine,” he says. “They’d call me ‘natural’ as if I’d never had to work hard.

“But when you sit down and analyse it, it’s a massive, massive compliment, isn’t it? It’s natural, or it looks natural, because of the hours and hours and hours, the monotony of doing the same thing over and over again, the same drills, the same exercises.

“That’s what you’re trying to do, make it natural, so it comes easy and you don’t have to think about it. When people say I was a natural goalscorer now, I take it as a big compliment. I worked very hard to be ‘natural’.”

That work came first on the streets of Toxteth. Fowler’s late father, Robert Snr, would take him to the all-weather pitch near the family home where they would work for hours on end, wind, rain or shine.

“There was this metal gate around the field,” Fowler remembers. “And what I’d do, I’d drop-kick the ball with my right foot, over and over again until it felt comfortable. Then I’d put the ball on the floor, run up and strike it off my right, over and over again.

“It sounds boring doesn’t it? It was never boring for me. I wanted to do it. I wanted to get better. I love the saying ‘repetition, repetition’ repetition’ because it’s true. If you want to master something, you’ve got to work at it.”

It meant that by the time Fowler burst into the first-team at Liverpool, aged 18, he not only had the confidence, but the skills to match.

“I look at the goals I scored with my right foot, particularly early in my career, and it shows the benefits of hard work,” he says.

“The same with heading. I am only 5' 9", but I scored a lot of headers. That came from the simplest of drills, throwing a ball up and jumping, throwing it against a wall and directing it. Working on timing and bravery, keeping your eyes open to meet it.

“Sometimes the old drills are the best ones!”

Getty

GettyFowler also benefitted from the figures he encountered when coming through the ranks at Liverpool. Kenny Dalglish convinced him to sign for the Reds despite his boyhood allegiance to Everton, Graeme Souness gave him his senior debut as a teenager, while the likes of Jan Molby, John Barnes and Ronnie Whelan were role models, senior players who had been there and done it.

It was the presence of Liverpool’s all-time record goalscorer, though, which helped accelerate Fowler’s development. He had grown up idolising a Scot in Graeme Sharp, but it was a Welshman who would have the biggest influence on him as a professional.

“I count myself very lucky,” Fower says. “With Ian Rush, I saw what was needed to be a real top-class centre forward.

“It wasn’t a case of him taking me aside and teaching me the game. I’d see it on the training field every day. I’d see his runs, the way he anticipated things, the way he’d alter his finishes depending on the situation. To watch and learn from one of the best ever, it was a privilege.

“He would give me pointers, but it was usually the simplest of things. He’d talk about how to time your run, how to bend a run, how to get yourself out of the defender’s eyeline, shooting across the goalkeeper, through a defender’s legs so the keeper is unsighted. It sounds ridiculously simple, doesn’t it? But it’s not.

“People talk about goalscorers as selfish, and it’s true that you have to be in some situations, but so much of a centre-forward’s work is about creating space for others, dragging defenders out of position, making runs, stretching the game, always being on the move.

“Rushie was the master of that. I’d have been mad not to listen and take it in. If you can’t take advice from him, then you shouldn’t be in the game.”

Fowler’s record at Liverpool was remarkable. In his first three full seasons he scored 98 goals, picking up the PFA Young Player of the Year in both 1995 and 1996. In an era of great Premier League strikers – Alan Shearer, Les Ferdinand, Teddy Sheringham, Andy Cole, Ian Wright, Stan Collymore – his star shone as bright as any.

“It gives me pride to have been classed alongside those kind of players,” he says. “I was a baby compared to them, wasn’t I?

“But I’ve always had this belief. I know what I can and can’t do, and I always had confidence. Let’s be honest, I wasn’t the same player throughout my career, but I always believed I could do it. I always felt I could score in any game.”

Getty

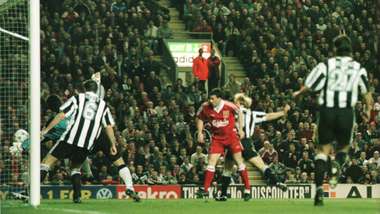

GettyGoal asks him to name his favourite strike. We are thinking of his four-minute hat-trick against Arsenal, perhaps, or that unforgettable strike against Aston Villa, where he sent Steve Staunton halfway up Anfield Road before smashing past Mark Bosnich. Brann Bergen, perhaps? Birmingham in the League Cup final?

There are plenty to choose from.

“It’s a good question!” says Fowler. “I scored a lot of important goals in my career, goals which gave me an awful lot of satisfaction, but my best goal, people might not agree, was at Charlton in the last game of the 2000-01 season.

“It was the importance which made it. Everything we achieved that year, winning three cups, it just capped it all off by helping us get into the Champions League. Liverpool hadn’t been there for a few years, so it was a really big game for us. We’d won the FA Cup on the Saturday, the UEFA Cup on the Wednesday and we needed to win down at the Valley to get third place.

“We were poor in the first half and it was 0-0. Then after half time one dropped to me in the box off a corner, and I just sort of helped it over my shoulder and in.

“It was maybe not as spectacular as some others I scored, but it was a clever finish. After that we were comfortable. When I look back, I always love that goal.”

We finish by talking about the modern game. Fowler played the majority of his career in a world of two-striker systems - he cites Collymore as his most fruitful partnership – but things have changed. The wide forward is king these days.

Does Fowler, a man with whom the No.9 shirt will forever be associated, lament this change in emphasis?

“No, not at all,” he says. “Formations and tactics may change, but some things never will. There will always be a place for players who can put the ball in the net.

“Who are the two best players in the world? And why? It’s because they score incredible amounts of goals, as much as anything else. [Robert] Lewandowski, [Harry] Kane, the same.

“No matter how the game changes, young kids will always want to be like those players, scoring goals and being the hero.

"That's all I ever wanted, anyway!"