When Naomi Osaka withdrew from the French Open after being fined for not speaking to the press – a decision she made due to the anxiety and stress that talking to the media gave her – she was criticised by fellow athletes and sports reporters alike.

Billie Jean King reminded Osaka of her ‘responsibility’ to the press, while one journalist branded her an “uppity princess” – with many more talking up the importance of the post-match press conference.

Osaka’s choice was made to preserve her own mental health, yet her emotional safety has been entirely disregarded in the ensuing conversation, with her critics keen to preserve an age-old media tradition instead.

When you’re an athlete, who cares about your mental health? It’s been an issue also prevalent in football for a long time - and continues to be.

When Stan Collymore checked into Roehampton Priory mental health hospital for depression in 1999, all his manager had to say was: “How can someone earning this much money a week be depressed?”

It is so easy to lose sight of the fact that the athletes we idolise are human, just as susceptible to pain and anguish as the rest of us. According to 2016 research, scientific studies on the extent of mental health problems in elite sport are rare. Mental health issues in sport are under-investigated and under-reported.

This could be related to the fact that there is a stigma around the importance of valuing emotional and mental wellbeing in the competitive arena - as we’ve seen in the furore over Osaka’s decision to forego a potential Grand Slam victory in favour of looking after herself.

Only recently has there been a public show of support for mental wellbeing in football by the likes of the FA, with the Heads Up initiative - led by the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge - launched in 2019.

Its launch came a year after a Professional Players' Federation survey discovered that more than 50 per cent of former players had concerns about their mental health following retirement.

And as we’ve seen with Osaka, in football, superstars are not immune.

Getty Images

Getty Images

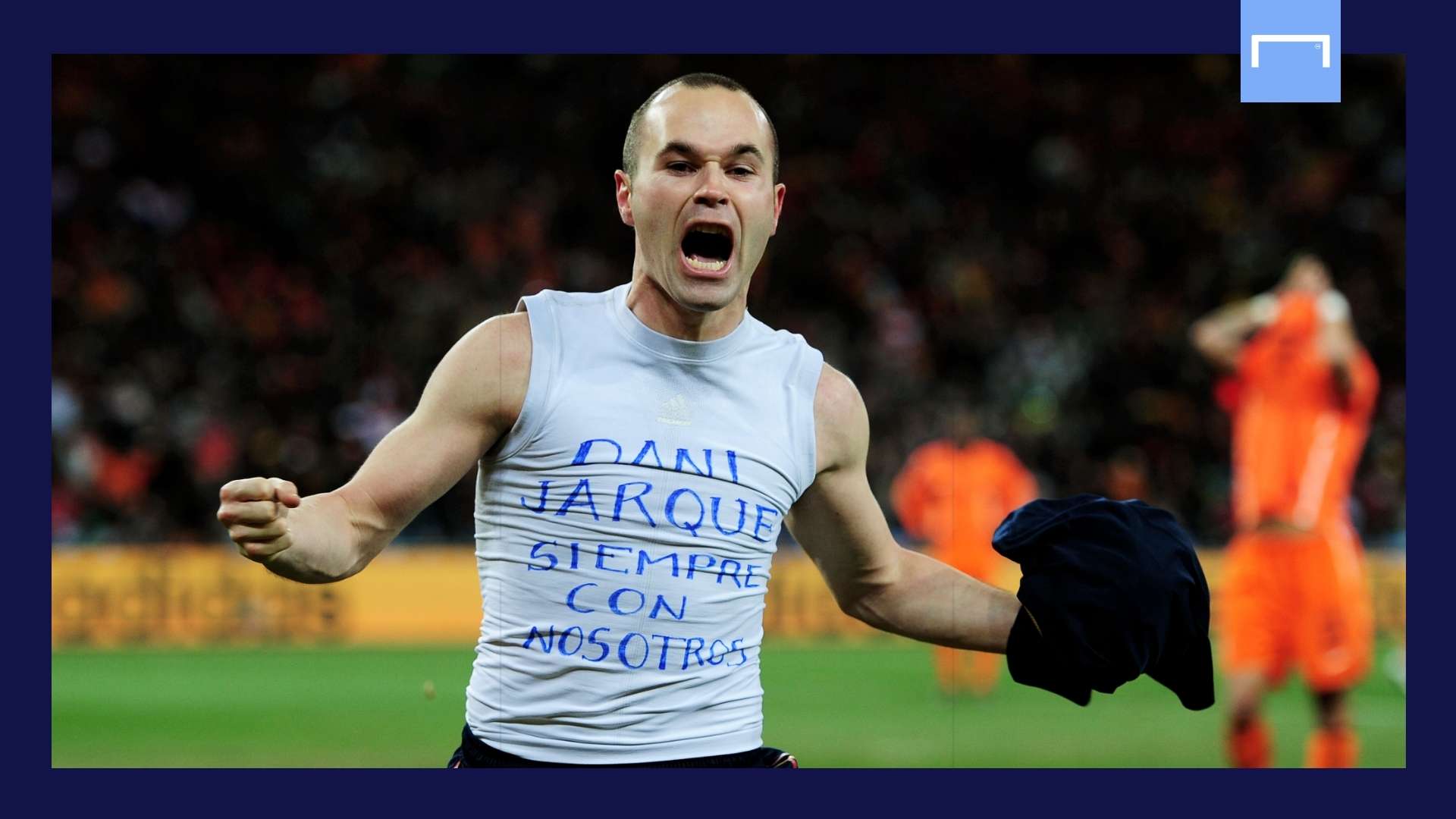

Andres Iniesta revealed that he suffered from depression prior to the 2010 World Cup following the death of his friend Daniel Jarque. In 2018, Michael Carrick admitted that he went through a depressive spell for two years following Manchester United’s defeat in the 2009 Champions League final. The same year, Danny Rose disclosed that he had been diagnosed with depression.

And then there are the tragic cases of Robert Enke and Gary Speed, who both completed suicide following depression.

“I think that there is a real reluctance to actually acknowledge this in sport,” Misia Gervis, a sport psychologist and professor at Brunel University London, tells Goal.

“We keep saying that the player is the problem and people tend to blame the individual. That it was just so-and-so it was just their own personal issues, rather than saying, well, what was it about the world that they are living in that significantly contributed to that?”

Gervis was appointed by the FA in 2002 to work as a consultant to develop courses for coaches with sports psychology. Back then, there was nothing psychology-focused in any of the coaching education programs.

“We paint these footballers as these superheroes. It probably says quite a lot about us that we can't accept their humanness and their human frailties. We want these people to worship, to hero-worship," Gervis said.

“I did some work with a manager and he was saying it's like living in these two spaces. It’s either: ‘I’m God if I win, or I’m the devil if I lose’. And there's nothing in between.”

For Michael Caulfield, a sports psychologist who has worked with both Premier League clubs and Championship clubs, it is crucial for the athletes to see him as a person completely separated from actual matchday duties - that whatever they might say, do or feel will have no consequence on their future at the club.

“I've never to this day taken part in any selection meeting for a player or not,” Caulfield tells Goal. “I don't even go in the coaches’ room. I want the players to know that I have no involvement in that side.”

Caulfield cites failure as the biggest struggle that a footballer can face. In football, where your worth is placed on how well you perform, too much pressure is placed on the individual. They may feel as if they need to constantly prove themselves to the detriment of their own mental wellbeing.

“Letting people down is the case,” Caulfield says. “That becomes the judgment issue. It's the fear of not being good enough. I think that was certainly the case with the England national team for years. And a lot of the players who played in the international team told me that they said they were more worried about the reaction that they got going on with the World Cup.”

According to Gervis, the psychological effects of a long-term injury can be one of the most devastating things to happen to a player. When you base your entire livelihood on your performance output as an athlete and you get injured, the road to recovery is a dark, desolate path.

“Psychological wellbeing will inevitably impact on how they’re playing,” says Gervis. “You can’t extrapolate one from the other. All long-term injured athletes should have routine psychological support.”

If a player is being sidelined with injury, they are isolated and alone, separated from the team physically and mentally. The feeling of separation is akin to standing still while everyone else goes past you, with the fact that your identity - the very core of who you are - is challenged.

“When you’re lying on the treatment table but hearing 24 sets of studs walk out across the concrete, going to training, it’s extremely difficult,” adds Caulfield.

“Even the word ‘rehab’ is so negative. It sounds like you're an addict.”

In Gervis’ research, the majority of first teams in the English football pyramid had no sports psychologist in the room when it came to dealing with a player nursing a long-term injury.

“You will have 10 video analysts, 10 physiotherapists and a part-time psychologist,” Gervis says. “That speaks volumes to me, in terms of where you put your priorities. Clubs usually hire sports psychologists on a part-time basis. If I’m working part-time, I achieve significantly less.”

Goal

Goal

While at Queens Park Rangers, one of the stipulations of Gervis’ work was that in the academy, every long-term injured player had to have individual conversations with the on-site team. This, Gervis says, is not the exception - it is the normal, and should continue to be the normal.

“Injured athletes will tell you that the difficult bit is the psychological challenge,” Gervis continues. “Physical is easy, since that’s where the support is. The emphasis is all in the body. But hello, what about the mind, emotions and feelings?”

Even the terms “injury-prone” or “susceptible to injury” popularised by the media are harmful descriptors for athletes. This constant labelling of how likely a certain player is and isn’t vulnerable to regularly picking up injury is a detriment to their psychological wellbeing, having the ability to impact their own road to recovery - both mental and physical.

“Fear of re-injury anxiety is prevalent in almost anybody who’s coming back from injury,” Gervis explains. “It means that you create muscle guarding. You may be doing some avoidant behaviour because this anxiety is showing up. You question the worst that could happen to your body, and then you’re more likely to be injured again. If you don’t address the psychological, you are creating fertile ground for re-injury to happen.”

Physios are not trained psychologists, and mental health is not their area of expertise – yet most players will only see a physio because it’s not culturally embedded in how things are done.

It has been increasingly more common for footballers to reveal their battles with depression following their retirement, since they would not have to deal with the aftermath while still an active player.

But retirement plays a massive role in a footballer’s wellbeing, as suddenly, their entire worth and value as a person - being on the pitch - is suddenly challenged.

For other former footballers, this transition can also be therapeutic. Steven Gerrard never won a Premier League title with Liverpool. As celebrated he is for his achievements as a dedicated captain, opposition fans will bring up his infamous “slip” against Chelsea during their 2013-14 title run that may or may not have squandered the title.

Events like these have the ability to traumatise a player for the rest of their lives. But Caulfield uses perspective as a means to get through his players. Gerrard could spend forevermore wondering what could have happened if he had never slipped, but instead, has found success as manager of Rangers, using his abilities as a leader into his coaching.

Getty Images

Getty Images

“Such is his resilience as both a player and now a coach that he is refusing to be denied by that one incident,” says Caulfield. “Both his triumphs and his disappointments will spur him on for the rest of his life. And who’s to say that one day he won’t go back to Liverpool?”

Osaka, meanwhile, stated that she had “suffered long bouts of depression since the US Open in 2018” - her maiden Grand Slam victory but one which was incredibly upsetting due to the reactions from the New York crowd after her defeat of favourite Serena Williams.

Caulfield has worked with Gareth Southgate, and cites the current England manager as another example of a former athlete refusing to be defined by their incidents as a player.

“Southgate could’ve been defined by that penalty miss against Germany, but he’s not, because both he and Gerrard want to write another chapter of their story. I encourage players to think in a long-term way, but it takes timing and trust. Do they want to keep reminding themselves of these horrible things, or do you want to remind them that there will be more opportunities in life? You have to deliver perspective at the right time.”

With male footballers in particular, there is also the issue of how acceptable it is to seek for emotional help without the fear of feeling “weak”. “As a sport psychologist, you have to ask yourself: are you in a culture where hegemonic masculinity is alive and kicking?” Gervis says.

“In an all-male environment, someone's behaving with anger. People who are angry or hurt are always vulnerable. You have to deal with the hurt person, not the anger. That’s why you need psychologists.”

So while substantial work still needs to be done to ensure better mental health protection for footballers, Gervis remains optimistic. “I have to be,” Gervis says. “Otherwise, what’s the point? I might as well go home and give up.”

And considering how affluent professional football clubs are, it is a surprising fact that in Gervis’ early research, it was discovered that not all clubs had mental health as part of their medical insurance.

As a preliminary step, the PFA should ensure that these measures are in place for all footballers, as simple structural changes could make a huge difference.

“Just imagine you're doing your job and you've got 10,000 people screaming at you, saying you're a piece of sh*t. You’d fall apart,” Gervis says.

“It's a difficult world to live in. Social media makes it a hundred times worse. We as spectators feel entitled to say all these things as if it wouldn’t, on some level, do damage.”

And yet people wonder why Osaka made the choice that she did. What we should be asking, instead, is how come it took this long for an athlete to come out in defence of their own mental health – and why we are so quick to vilify them for taking that vital step.