By Jonathan Smith

It was not that long ago that European fans simply referred to “Manchester” when they talked about the team from Old Trafford.

Seemingly, there was only one team from the city. How things have changed.

“Not in my lifetime,” Sir Alex Ferguson said 10 years ago when asked if United would ever go into a Manchester derby as underdogs. Now his former club are so far behind Manchester City that, after just eight matches of the new Premier League season, they are not even considered credible rivals in the title race. Remarkably, bookmakers are offering shorter odds on Ole Gunnar Solskjaer’s side being relegated than they are on them winning a 21st league trophy.

These days, the more pertinent question is how long will it take United to catch up to their city rivals? In the space of a decade, City have leapt ahead in almost every aspect, winning four titles to one while becoming one of the most feared sides on the continent. The gap has not been this wide since the turn of the century, when United were crowned champions of Europe while City needed a penalty shootout to secure promotion out of the third tier of English football.

The blue side of Manchester now does almost every aspect of modern football better than their cross-town rivals, be it management, building of a first-team squad, scouting, academy or infrastructure. Take women’s football as an example. City had won a Super League title before United had even organised a team to play a competitive match.

United still have the money, the fanbase and the power, but unless they start addressing their problems on the pitch, that will start to wane too. But just how has the power shifted so dramatically in the space of a decade?

The obvious answer is, in simple terms, financial.

Sheikh Mansour Bin Zayed Al Nahyan took over City in 2008 and has invested more than £1 billion in first team personnel alone in a bid to turn to the club into the best on the planet. United may have also invested heavily in their own squad, but not to the same level. They continue to turn record revenues - leading the way globally in terms of commercial success - but also spend cash servicing a debt from the buyout by American owners, the Glazers, in 2005.

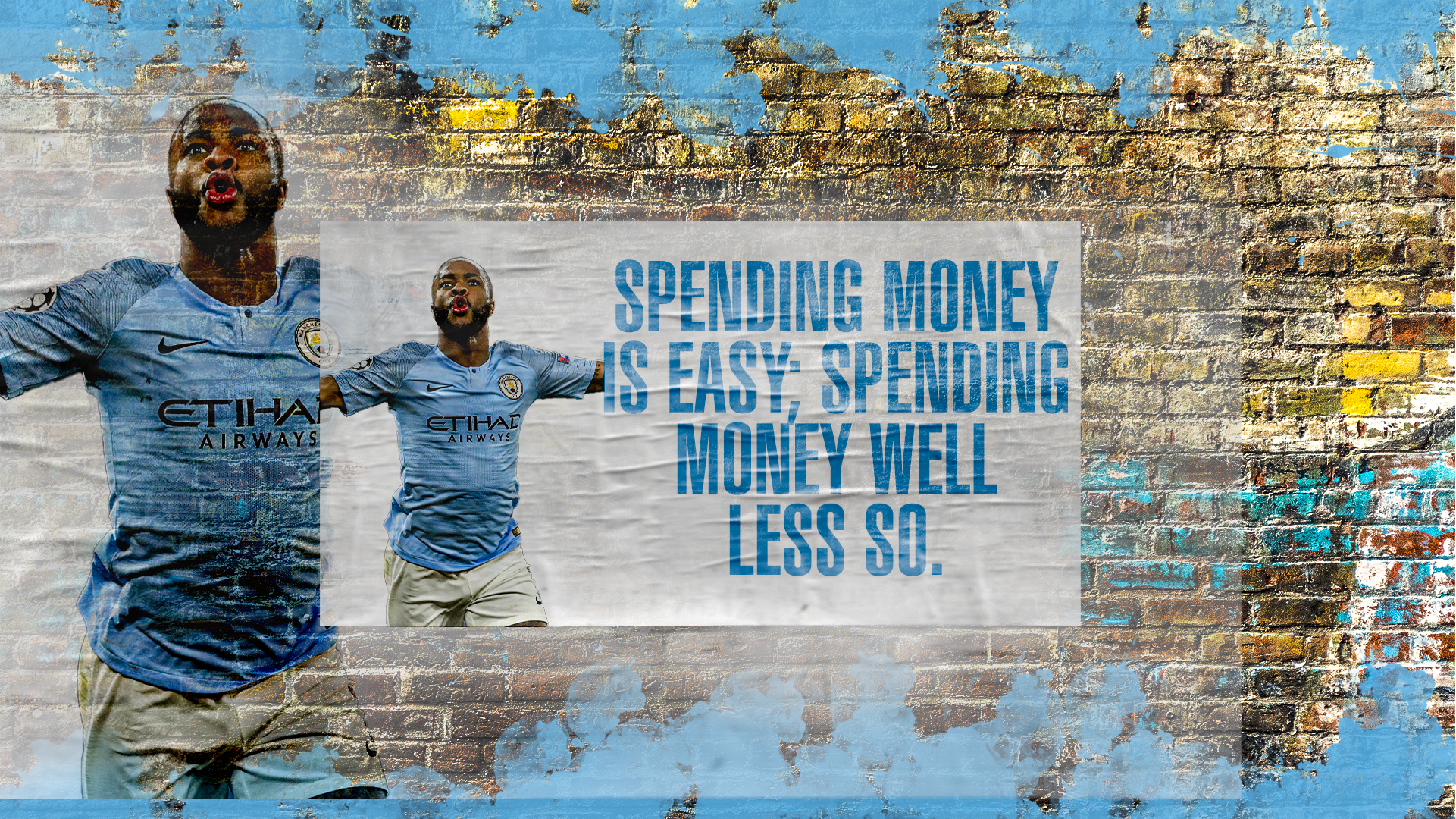

To put the change in fortunes down to pure cash, however, ignores the way that money has been spent. Over the past 10 years, City have a net spend of around £1.067bn ($1.374bn) in transfer fees compared to £682m ($878m) at United. That difference of £385m is a sizeable chunk that would put any club in with a chance of taking on the European elite. But simple figures cannot illustrate how well that money has been spent.

In September, football website transfermarkt put the value on City’s squad at £1.15bn, with United’s valued at a comparatively paltry £677m. That difference of £473m suggests that City are far wiser when it comes to investing in their squad.

“The club stays; the people do not. People need to be successful, otherwise others will come,” director of football Txiki Begiristain explained about City’s transfer policy in September 2018. “They are not coming here just to enjoy life - they are coming to fight to win. If you win, you need to bring someone in to create competition. If not, you have to improve some pieces.”

City have come a long way from the initial takeover. When Sheikh Mansour bought City, Ferguson’s United side had just won the second of three successive Premier League titles. City had finished ninth, with a points tally that left them closer to the bottom three than the champions after a demoralising 8-1 defeat at Middlesbrough on the final day of the season.

The Abu Dhabi owner was initially lavish with his spending, bringing in Real Madrid superstar Robinho on deadline day while players such as Emmanuel Adebayor, Wayne Bridge, Carlos Tevez and Craig Bellamy helped negotiate the rise from mid-table mediocrity to the elite of the top four. A decade on and the two squads look very different. Spending money is easy; spending money well, less so.

Begiristain has scoured Europe and South America looking for stars in the making and is far less likely to attempt to negotiate with Europe’s best clubs compared to United. Taking a chance on a promising player in his early 20s makes it more likely that a club can enjoy his best years, especially if he goes on to become one of the best in the world. Leroy Sane, Gabriel Jesus and Raheem Sterling, who were all bought when in their early 20s, represent a forward line that cost close to £100m.

They are now worth more than three times that.

Sources at United admit that they were slow to update their scouting network, allowing other top European clubs to establish contact with players and agents long before they were on the scene. They have now restructured their scouting department, and signalled a new strategy in the summer with the buys of Harry Maguire, Aaron Wan-Bissaka and Daniel James - promising players that should improve while signed from 'lower-tier' clubs. That, though, was only done after the scars from a huge number of expensive flops had already been created.

“They now need to fix a style and fix a way of recruiting,” former United defender Gary Neville said recently. “It is going to be painful and the board are going to need to hold their nerve.”

In the past five years, United have made four of the top 25 most expensive signings of all time - Paul Pogba, Maguire, Romelu Lukaku and Angel di Maria. City do not feature anywhere on the same list.

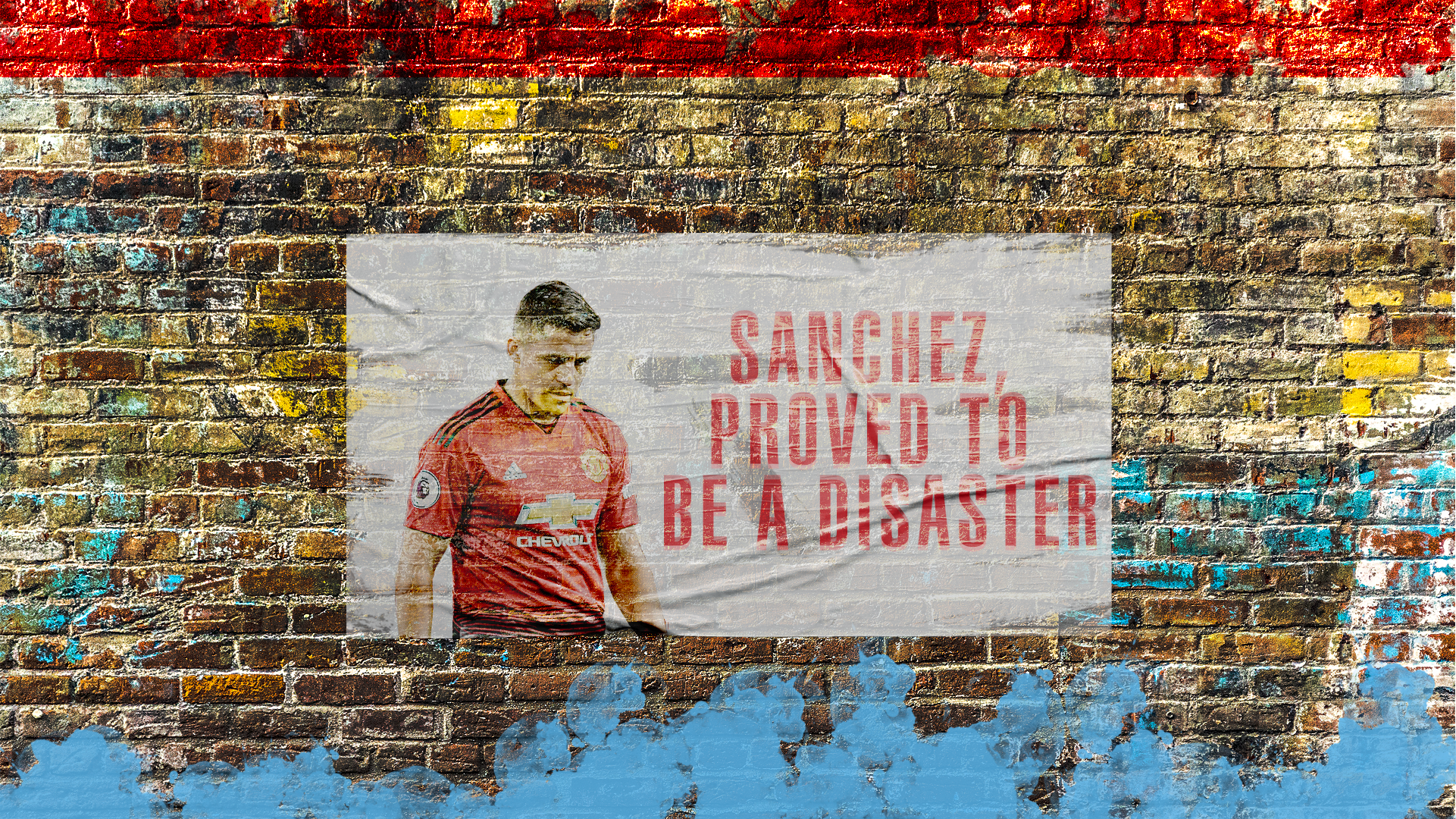

No transfer personifies the differences between the two clubs’ strategies in the market more than Alexis Sanchez. City had been tracking the Chile international’s contract situation at Arsenal for some time, but pulled the plug on any prospective move when United’s interest turned the bidding process into an auction for a player who had just six months remaining on his deal in north London.

In January 2018, Sanchez was unveiled to great fanfare by United, who wanted to show off their transfer coup. Sanchez, though, proved to be a disaster, scoring just three times in 38 Premier League appearances and now finds himself out on loan at Inter with United still paying a huge chunk of his £25m-a-year contract.

City’s transfer strategy is carefully planned - carrying out due diligence and assessing the personality of everyone who joins the club, including players. In 2013, following the appointment of Manuel Pellegrini as the club’s new manager, City said they would “develop a holistic approach to all aspects of the football club”. It was a statement that caused a few giggles around the football world for its new-age management-speak, something that is not welcomed in an environment where the no-nonsense approaches of Ferguson or Jose Mourinho were seen as more productive.

In truth, City had already been working along those lines previously, but shied away from being so open about it. They had appointed Brian Marwood as a de facto director of football but thought giving him that title would open them up to ridicule given English football’s resistance to the role, despite its success on the continent. His official title was football administrator, but in truth he was the mastermind behind the signings of a core of players, including David Silva and Sergio Aguero, that has served the club so well for the best part of a decade. Marwood was also behind improvements to the City academy and long-term infrastructure of the club that have proven to be the building blocks for where they now find themselves.

A thread runs through the club’s academy with a playing philosophy that goes from primary-school age to the first team. Players are placed in one of four statuses - incubating, emerging, prime or twilight - so that coaches can see instantly where there are any potential gaps and address them.

When asked by the Daily Telegraph what the difference was between his former clubs and both City and Liverpool, ex-United manager Mourinho said: "I think the structure of the clubs When you look at City, for example: the owner, Ferran Soriano [chief executive], Txiki Begiristain, Pep Guardiola, Pep’s staff and then the players."

"This looks like harmony, empathy, chemistry, quality, sharing the same project, sharing the same ideas."

While City adopted a new approach a decade ago to not only topple United but to be one of the best in Europe, United were still under the control of the iron fist of Ferguson and felt there was no reason to change things. The Scot was a phenomenon, overseeing unrivalled success as his ever-changing squad won 13 Premier League titles, five FA Cups, four League Cups and two Champions Leagues.

Possibly his greatest achievement, though, was to wrestle the title back from City to Old Trafford in 2013 with an ageing squad boosted by the arrival of Robin van Persie. At the end of that campaign and facing the task of having to build another team capable of challenging for titles consistently, he decided to call time on his long reign and retire.

It did not prompt, however, any change or modernisation in the way that the club would do business. Ferguson handed the keys to the “Chosen One”, David Moyes, along with a six-year contract and a mission to carry on where he left off. It was mission impossible. Moyes was sacked 10 months later.

From there, United have stumbled from manager to manager with knee-jerk appointments rather than via a far-sighted strategy. Louis van Gaal was the technical one. Mourinho the special one who had the spine to take on Guardiola. Now it is Solskjaer, the emotional one who can tap into the feelings of the fans.

Conversely, at City, everything was in place to attract the world’s best coach in Guardiola to succeed Pellegrini in 2016. And there are already potential options being identified for when the Catalan eventually leaves the Etihad Stadium.

At United, Solskjaer’s future is far more precarious, but there are no obvious candidates to replace him; no carefully crafted plan. Ed Woodward, so successful when in charge of the club’s commercial departments, maintains control of the hiring and firing; signings and non-signings. He has faced criticism, from those both inside and outside Old Trafford, for having too much responsibility for the identity of those in the playing squad, spending summers vetoing names on manager’s wanted lists while allegedly chasing players that his coaching staff do not want.

“They've cocked it up over many years,” Neville said of the board.

“They're responsible for this poor recruitment. They've gone for completely different styles of managers. They've now gone with Ole Gunnar Solskjaer and a completely different style. If you change direction every two years and invest £250m along the way with each manager, you're going to have problems.”

Whether United will now bring in their own director of football to instil unity between the board and the coaching staff remains unclear. Senior figures have suggested that a search for a technical director became the priority when the summer window of 2019 shut, but as yet the position does not exist. A host of former players such as Rio Ferdinand, Nicky Butt and Edwin van der Sar have been linked with the role, but Woodward cryptically told investors in September that they are “reviewing and looking at the potential to evolve our structure on the football side”.

He added: “Much of the speculation around this type of role revolves around recruitment - an area that we’ve evolved in recent years. As we’ve already mentioned, we feel the players we’ve signed in the summer demonstrate this approach is the right one.”

While the first team remains a long way behind City, United are at least starting to make headway in younger age groups. An area of the game previously dominated by the Reds for decades after legendary youth sides produced the “Busby Babes” and the “Class of ’92”, they have been usurped by City, who offer a high-quality education as well as a superior coaching environment. Former United players Andy Cole, Phil Neville, Darren Fletcher and Van Persie even sent their own children to City’s academy. Such was the gulf in class, City won derbies at three different age groups 5-0, 6-0 and 9-0 in the space of a couple of days in 2016.

While City and Chelsea have led the way in youth development, finding a pathway to the first team has proven difficult, though a transfer ban has at least helped Frank Lampard bring about a youthful revolution at Stamford Bridge. United, meanwhile, have put more investment and resources into their academy structure, and are now starting to see that bear fruit on their first team, particularly when compared with their cross-city rivals.

Marcus Rashford and Scott McTominay are first-team regulars while Mason Greenwood, Axel Tuanzebe, Tahith Chong, Brandon Williams, James Garner and Angel Gomes have all made debuts over the past two years. A closer working relationship between Solskjaer, first-team coach Kieran McKenna and head of development Butt has delivered a more cohesive strategy lacking in other areas of the club.

City, who lost Jadon Sancho to Borussia Dortmund due to a lack of senior opportunities, would argue that they are looking for the sort of quality to challenge the world’s best players rather than automatically fill gaps when higher-profile players begin their demise. Phil Foden is still fighting to become a regular despite being the poster-boy for the club’s academy. Behind him, Eric Garcia and Taylor Harwood-Bellis are training with the first team. All seem certain for a career at the very top level, even if it has to be away from the Etihad Stadium.

United, meanwhile, continue to lead the way off the pitch, with revenues hitting a record £627m ($807m) for the year to July. But a lack of success on the pitch is starting to hit even that. Missing out on qualification for the Champions League has prompted predictions that revenue and profits will fall this season, particularly given outgoings continue to grow, with last season’s wage bill up 12.3 per cent.

City, meanwhile, are making steady progress - joining United as the only British clubs to surpass £500m in annual turnover when last year’s figures were reported. The spectre of UEFA’s Financial Fair Play investigation, of course, hangs over the club’s every financial move, though they continue to strongly deny any wrongdoing amid claims they could be banned from entering the Champions League in the near future.

And it is a Champions League victory that remains City’s top target and after two quarter-final exits in as many seasons, Europe is the only area where the club has come up short. United, comparatively, would just like to be back in the competition that 10 years ago would have been unthinkable for them to have missed out on competing in.

In a decade of such a drastic change that few people would have dared predict, Mourinho - one of the greatest managers of the modern era - summed up the differences between United and City best when he said: "I won eight championships and three Premier Leagues, but I keep feeling the second [to City at United in 2017-18] was one of my biggest achievements in the game."

If the two clubs continue on their current trajectories, with time the Portuguese will only be proven more correct.