Back to the future: Sonny Pike returns to Ajax

The former child prodigy discusses mental health in football, drawing upon a past in which he went from stardom at 12 to burned out by 18

Sonny Pike shifts uncomfortably in his chair. “If you'd asked me to do this even five years ago, there wouldn’t have been any chance,” he confesses. “I'd have run for the hills.”

But here he is, sitting in the café at Ajax’s famed youth academy, ready, willing and now able to talk about how he went from lining out for one of the most prestigious clubs in world football to suffering a nervous breakdown.

Before he was even out of his teens, he had met his idols, the heroes of Ajax’s 1995 European Cup-winning side, appeared on the seminal British comedy show ‘Fantasy Football’ and fronted numerous advertising campaigns for global brands such as Coca-Cola and McDonald’s.

"A bit of me wishes I'd never got involved in any of that,” Pike, now 35, sighs. “I just wanted to play football but I got swept along in that side of things. That wasn't my plan at all.

“I didn't get into football to become well-known; to become a celebrity. I just wanted to be a footballer.”

Instead, Pike became an advertising tool, a poster boy for the new Premier League era who was chewed up and spat out when he had served his purpose. He was exploited by avaricious agents, ad men and even his own father.

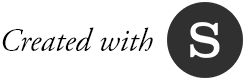

By the age of 18, ‘The new Ryan Giggs’ was emotionally drained, unable to even watch football – let alone play it.

Finally, though, two decades on, he has returned to Amsterdam to come to terms with his past so that he can warn others about the ugly side of ‘The Beautiful Game’.

Pike was born and raised in Enfield, a large London borough. It was there that he first fell in love with the game, spending hours amusing himself at home by trying to kick a small ball through the gaps in his spiral staircase.

“I’d get it in once in a while,” he insists, smiling broadly at the memories, “And I’d run around celebrating. I’d be buzzing for days!”

He joined local team Enfield Colts at six years old, playing his first few games in goal before quickly realising that it was not the position for him. “I wanted to be more involved,” he explains. “Plus, when it’s cold and raining, it’s no fun standing around in goal all game!”

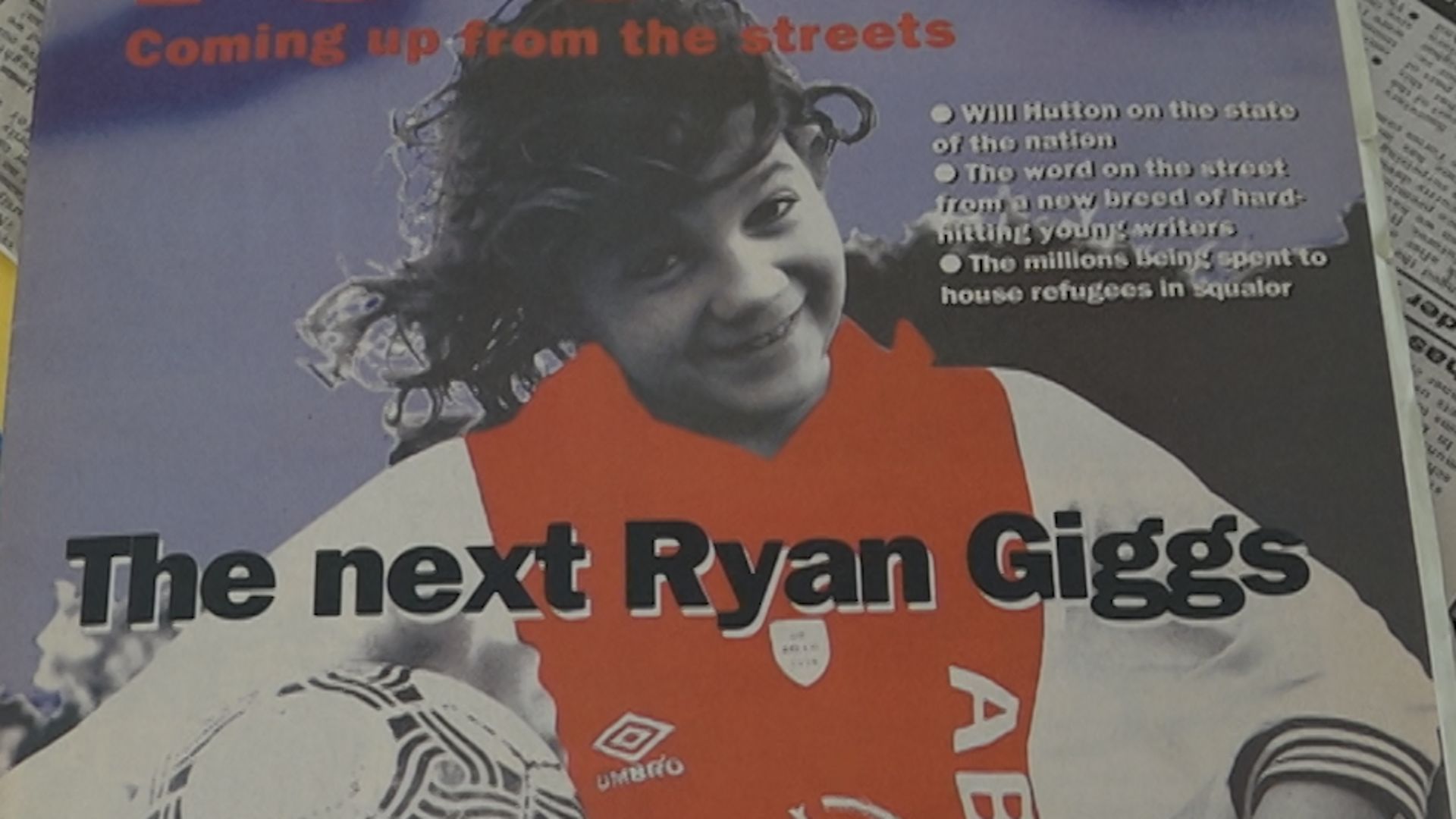

As a result, he moved up front and immediately felt right at home. Pike stood out from the rest of the kids – and not just because of his long locks. By the age of 10, he was playing for Enfield Football Club and “scoring goals for fun”.

Trying to explain to my little girl why I have been on radio the last week looking through old videos 🙈⚽️😀 pic.twitter.com/XVvVipBLVn

— Sonny pike (@Sonnypike01Pike) March 3, 2016

“I remember one game we played and we won 14-2 and I think I scored 13 of the goals,” he exclaims. “I just used to pick up the ball and run straight for the goal."

It was a simple but effective tactic, and one that drew the attention of not only several clubs, but also various agents. “I had four or five by the time I was 14,” he reveals. “And not just a guy from around the corner either; guys representing Premier League players."

However, it was a trip to Netherlands with Enfield – not an agent – that would pave the way for the move that changed Pike’s life forever.

“When we came back it was mentioned to me about going back out there for a trial with Ajax,” he explains. “They asked if I'd like to do it and I said, ‘Why not? It'd be a great experience.’

“At that time, Ajax were like Barcelona. They won the Champions League the year I went over [1995]. It was every kid's dream.

“When I picture now some of the things I saw… Watching the first team is something I’ll never forget. There was [Frank] Rijkaard, [Marc] Overmars, [Jari] Litmanen, the De Boer brothers [Ronald and Frank]... And I remember thinking, 'This is actually unbelievable.'

“The whole experience was mind-blowing. Just being involved, them giving me the tracksuit with the little badge on it and coming out and training on the astro turf - it's what dreams are made of.”

Unfortunately, Pike’s career slowly turned into a nightmare. At Ajax, he was already beginning to feel the strain of the constant media work, both physically and mentally.

“I didn’t stay that long and I think that was because what made my time here different to most other kids was the attention I got,” he explains.

“I remember the first game I played in. I think it was like 2 o'clock in the afternoon. And I remember the night before thinking, 'God, this is such a massively important game!'

“But I had to be up at 5 o'clock in the morning to do a documentary. I was running through the middle of Amsterdam, doing tricks.

“I had tonnes on, so it wasn’t just football for me. I got caught up in the media and celebrity side of things. It was non-stop.

“I remember doing an advert and my legs were raw from keeping the ball up for hours on end. It was quite cold and I remember saying, 'I've had enough of this now.'

“But they were like, 'You're getting paid; you have to carry on.' I was in bits. I had to go home and have a warm bath. So, that was tough. And it happened quite a few times."

Pike was also recognised wherever he went; he had become a famous young face within the footballing community. He entertained the crowd before the 1996 League Cup final between Aston Villa and Leeds United at Wembley and was twice named Sky Sports’ youth team footballer of the year.

"When I was getting my award the first time,” he recalls, “Alex Ferguson is in the crowd watching with [David] Beckham and all of these other players, and they're all going 'Sonny! Sonny!' That's hard to explain to people.

“As a kid, that was tough to take in because they were heroes to me. I wanted to be just like them and there they are giving me praise. And I'm thinking, 'I've not even made it yet.' Everything was just going so fast.

"I remember going to a competition in Denmark. I was on a boat and, as random as you like, two American kids came up to me with Shoot magazines saying, 'Sonny, Sonny, sign it! Sign it!'

“They were my age but I was in the magazine they're asking me to sign, which was surreal.”

However, even that bizarre experience was nothing compared to the day he met former Ajax boss Louis van Gaal.

“I was in the café with Ton Pronk (the Ajax scout who looked after him during his time in Amsterdam) and my dad, and we were talking away, having a cup of tea,” he reminisces.

“Then, Louis van Gaal just came over. Tom and him knew each other, so they were talking. But then he walked off and came back over to give some biscuits.

"I remember looking at them, opening them up and thinking, 'Yeah, I'll have some of that!'

“He said nothing, though, and my dad didn’t know anything about football, so he said, 'Who's that?' And I was like, 'That's the first-team manager!' I was all excited.

“I also remember to Rijkaard one day, asking him a few questions. He was like a hero and I was thinking, 'Oh my god, I've been watching him on the telly, and now he's coming towards me.’

“And I'm not just asking him for an autograph, I'm having a conversation with him. It was a lot to take in!"

Ajax Youth Academy an experience I will never forget (Dutch TV reason for the funny music in background) 😂⚽️👌 pic.twitter.com/WnT57FMmli

— Sonny pike (@Sonnypike01Pike) March 7, 2016

Although Ajax offered him a full-time place at their academy, Pike returned to England to join Leyton Orient, where his media commitments only increased.

Still, the pitch offered sanctuary and he was poised to join Chelsea until he found himself at the centre of a scandal that brought his whole world crashing down.

Pike’s father, Mickey, had pushed him into participating in an episode of the Channel 4 documentary series 'Fair Game' that he thought would be about his exciting fledgling career.

However, ‘Poaching & Coaching’, which aired in May 1996, was instead an expose on how clubs were making illegal payments to parents in order to sign young players.

“When it was broadcast and I saw what it was actually about, I was in total shock,” he says.

“I was watching it in the pub with my old coach Terry [Welch] and I was just bemused. I actually walked out into the street and was just lost, thinking, 'What's gone on here?'

“As time went on, I tried to retreat and start from scratch because I couldn't play for either club. I ended up being banned for a year.

“I was gutted because I thought I was going to play for Chelsea. So, that was tough. I took a big blow mentally and I never really recovered, to be honest with you."

The documentary resulted in him cutting all ties with his father, whom he saw for the last time 20 years ago.

Football had helped Pike cope with the earlier break-up of his parents’ marriage but, even when his ban had ended, he found there was no escape from all of the drama surrounding him.

As the long-haired kid with the cherubic face who had had his legs insured for £1 million and mingled with the likes of Ian Wright and George Best at awards ceremonies, he was instantly recognised wherever he played. There was nowhere to hide and the pressure to perform became too much to handle.

"I'd turn up for training and the kids' eyes widened, wondering 'What's he doing here?' They were a bit strange with me,” he says. “But I just wanted to blend in with them. I just wanted to get back to playing football. I didn't want to be known as that sort of flash character people thought I was.

"After I'd stopped talking to my dad and the plan was to get back into playing football and hopefully find a club. I ended up going to QPR and then Crystal Palace.

"At QPR, I was thinking, 'This is my chance to get back on track.' But I was in the dressing room before games feeling so nervous and the tension had gone through the roof because the expectation was massive.

“I was going through so much other stuff at home. Mentally, there was so much going on, and I struggled because I couldn't really focus or concentrate or be the same I was.

@MalleyFrancis @IanWright0 "what's happened to Sonny Pike? @Sonnypike01Pike pic.twitter.com/GlGN77QBS9

— Sonny pike (@Sonnypike01Pike) February 21, 2016

“I was even nervous in training. I’d always been so laid back on the pitch, I used to forget about a lot of things that were going on. I used to lose myself a little bit when I was playing football.

“But I found when I went back that as soon as I got onto the pitch, I felt the tension and the pressure. I was hiding. I used to be saying, ‘I want the ball’. But when I went back I just didn't want to be known. My attitude had changed.”

Pike finally cracked while representing Palace in a youth game against Tottenham, tipped over the edge by a couple of seemingly innocuous errors.

“The ball came to me a few times and my touch was off,” he remembers. “Then, it came to me again and it hopped over my foot.

“People watching might not have thought much of it but for me, it blew up into a big deal. I'd had a few poor touches and I felt under pressure.

“So, I just started walking off the pitch. I never even said I was injured. I walked straight off.

“The coach was looking at me and I was just like, 'Let me go.' I walked straight into the changing room and just sat there, wondering what was going on.

“It was tough. I was only about 15 or 16 and, honestly, I still feel it now. That was the last game I played for Palace. I stopped playing altogether for a few months.”

George best would of been 71 today ⚫️⚪️⚫️⚪️ not forgotten 🎂⚽️ pic.twitter.com/8gR9GYPmse

— Sonny pike (@Sonnypike01Pike) May 22, 2017

Pike was eventually persuaded into joining Stevenage by a friend – but not because he wanted to continue playing football, solely because he felt he had no other options.

“I thought to myself, 'Do I really want to put myself through this anymore?' But I didn't know what else to do,” he admits.

“I sat in my bedroom thinking, 'If I'm not going to be a footballer, what am I going to do?' I had no plans, no nothing. It wasn't like I could do this or that. I'd missed quite a bit of school.

“So, I went to Stevenage. But, even when I was there, it was no longer in my mind, 'I want to be a football player.' That had gone. Gone.

“I wasn't thinking, 'If I do well here...' I was an empty shell. I wasn't in the frame of mind to become a football player.

“I went there and did my bit but I enjoyed the social side of it more than playing. I had a great laugh with the boys on the team. But, mentally, I wasn't there."

So, Pike quit. Several top clubs offered him the chance to kickstart his career but while the talent was still there, the desire was not. At just 18, he was done with football.

“For five years, I didn't kick a ball, or even think about the game,” he reveals. “I didn't know what to do with myself, so I just went out with my mates, like a normal kid at that age, I suppose.

“But I got myself in a few positions I shouldn't have. I was taking a lot of bad decisions. I just wanted to feel normal. I didn't want be known as ‘that long-haired kid from Ajax’ any more.

“I just wanted to blend in with the boys. I was in a bad way. I was struggling mentally and didn't know what to do.”

He was suicidal. Thankfully, the birth of his daughter Freya changed everything, inspiring Pike to secure a taxi-driver licence so that he could earn a steady wage to provide for his new family.

Big fun run with my girl and we are off 🏃🏃🏃🏃 pic.twitter.com/PTT2h7Epqb

— Sonny pike (@Sonnypike01Pike) October 30, 2016

“When I held on to my little girl in the hospital, I just thought. 'I’ve got to pull my finger out here, get on it and do something properly,” he explains.

“So, that's when I decided I'm going to do ‘the knowledge’ (the exam to become a taxi driver), get my own job, get some security.

“Since then, I've been making these little steps, got myself in good spirits and I'm doing alright now. I've got my kids, got married and my house. I'm just enjoying normal life."

However, Pike still wanted to address his past so that he could start building an even brighter future for himself, his wife Rosie, daughter Freya and recent arrival Beau.

His run he ragged this week.. 😍 pic.twitter.com/mSOzaFwnAn

— Sonny pike (@Sonnypike01Pike) August 22, 2016

Therefore, returning to Amsterdam was necessary. But nonetheless difficult. When he was asked at one point to do some flicks and tricks for the camera, it brought back some bad memories.

“I was quite blunt with the crew,” he admits. “I said no, as I've got to make sure I do the right thing by me. I’m in control now and I told them that it wasn’t for me.

“So, it's been a gradual process. It feels weird being here, I'm not going to lie, because everyone knows me and says to me, 'You're the long-haired kid who played for Ajax.'

“It feels surreal but I'm quite proud of myself in a certain way because I know I'm doing this for the right reasons.

“It’s also brought back some good memories too. And I've noticed that the more I've been talking, the better it's made me feel.

“It's making me enjoy football a lot more. I'm watching a lot more than I used to. I’ve found that talking's helped me a lot."

The goal now is to help others. As he finally feels comfortable telling his story, he plans to release a book detailing his experiences next year, while he has started visiting youth academies in order to help aspiring footballers cope with the pressure that very nearly broke him.

"I think I sort of rebuilt myself,” he muses. “That's given me the strength to come back and have the balls to go talk to the kids, and the press again.

“Even a couple of years ago, I was still dealing with things myself. But I think by helping myself first of all, I’ve now put myself in a position to help others.

"I feel very protective of the young players because of my own experiences. I can understand the pressure, so I’d like to do what I can to alleviate that pressure and get a bit more understanding out there.

“The main thing with the mental health side of things is that you can't see it. It’s like a blocked pipe: the pressure just builds up and then bursts if you don’t have a release.

“I was talking to Arsenal the other day and they wanted to bring the parents in as well and I said, ‘That's a great idea. We can get everyone talking and working together.’

“Adults everywhere struggle with mental health so how are kids supposed to deal with it if they’re left alone?”

Pike felt alone for many years, despite the best efforts of his mother Stephanie. As a result, he doesn’t want to dissuade kids from playing football. He just wants to ensure that they have a support network; someone to confide in.

“I don't want to be turning up telling the kids they're not going to make it as a professional,” he insists. “That's the last thing I want to do. My mission is to tell kids to chase their dreams.”

Indeed, his dreams took him all the way to Amsterdam. And while the chubby cheeks are now partially covered by a beard, that beaming smile still shines as brightly as ever before as he looks around the Ajax academy and remembers Rijkaard, the De Boer brothers and, most of all, those biscuits.

Because of those unforgettable memories, he’d happily support his own kids if they choose to pursue a career in football.

Don't care what I am doin today as long as I with these, everybody hav a nice day in there own way#HappyFathersDay pic.twitter.com/ObEkS6FnwZ

— Sonny pike (@Sonnypike01Pike) June 19, 2016

"My little boy is three and my little girl is eight. They both like football. My little boy plays indoors all the time,” he enthuses.

“I watch him now running around kicking a football, shouting 'Ajax! Ajax!' It’s weird. But I'll always be there whether my own kids win, lose or draw. That's the bit that keeps me going, if anything.

“I find myself sometimes even thinking, 'If they're ever going to be in a position where they're struggling, I can't wait to be there.'

“Finding myself almost hoping for that sounds a bit mad! But the thought of that… I can't wait. I'll be there for them and they’ll never have any worries.”

With that, Pike finally eases back into his chair, finally looking at peace with his past, and himself. He may not have become a footballer but he's clearly enjoying being a good dad.