Muller and Germany's World Cup machines

By Ronan Murphy

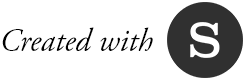

Bundesliga runners-up Schalke come from the heart of Germany’s Ruhr valley, with their 114-year history tracing back to the club’s early days in Gelsenkirchen where the team was largely comprised of miners, who lived in the

Schalke borough of the "city of a thousand fires." Each season, they compete in the Revierderby against regional rivals Borussia Dortmund, a team with a similarly-lengthy backstory, having been formed in a pub and named after

a local beer.

Even before the start of the 20th century, Gelsenkirchen and Dortmund have been known for their industry, producing coal, steel and beer for Germany and abroad. In 2018, the region is still known for its production lines, and with solar

power replacing coal, their focus has turned elsewhere, to the development of football players.

Leon Goretzka is one such talented young player, having been signed by Schalke as an 18-year-old from local side Bochum. S04 turned him into an international-quality player, who now has an Olympic silver medal and Confederations Cup title

to his name by the age of 23 as he heads to the World Cup with Joachim Low’s talented squad after agreeing to join Bayern Munich. There he will join goalkeeper Manuel Neuer, another of Schalke’s academy products.

Germany’s knack for producing talent is far from confined to particular clubs, with assembly lines of players throughout the country. Bayer Leverkusen (pharmaceuticals) and Wolfsburg (automobiles) are clubs formed by factory workers

but their home cities are now synonymous with football as much as they are with manufacturing.

At the 2014 World Cup, Bayer Leverkusen’s Christoph Kramer was announced as a surprise starter for Germany following an injury to Sami Khedira in the build-up. The full-back was unfortunately forced off with concussion, but was

an unexpected World Cup winner, having been told as a 15-year-old that he would not make it as a footballer because of his height. Eight years later, the then on-loan Borussia Monchengladbach midfielder lined out for Die Mannschaft in

the World Cup final, having grown to 6ft 3in (191 cm) tall and developed into an international-quality player.

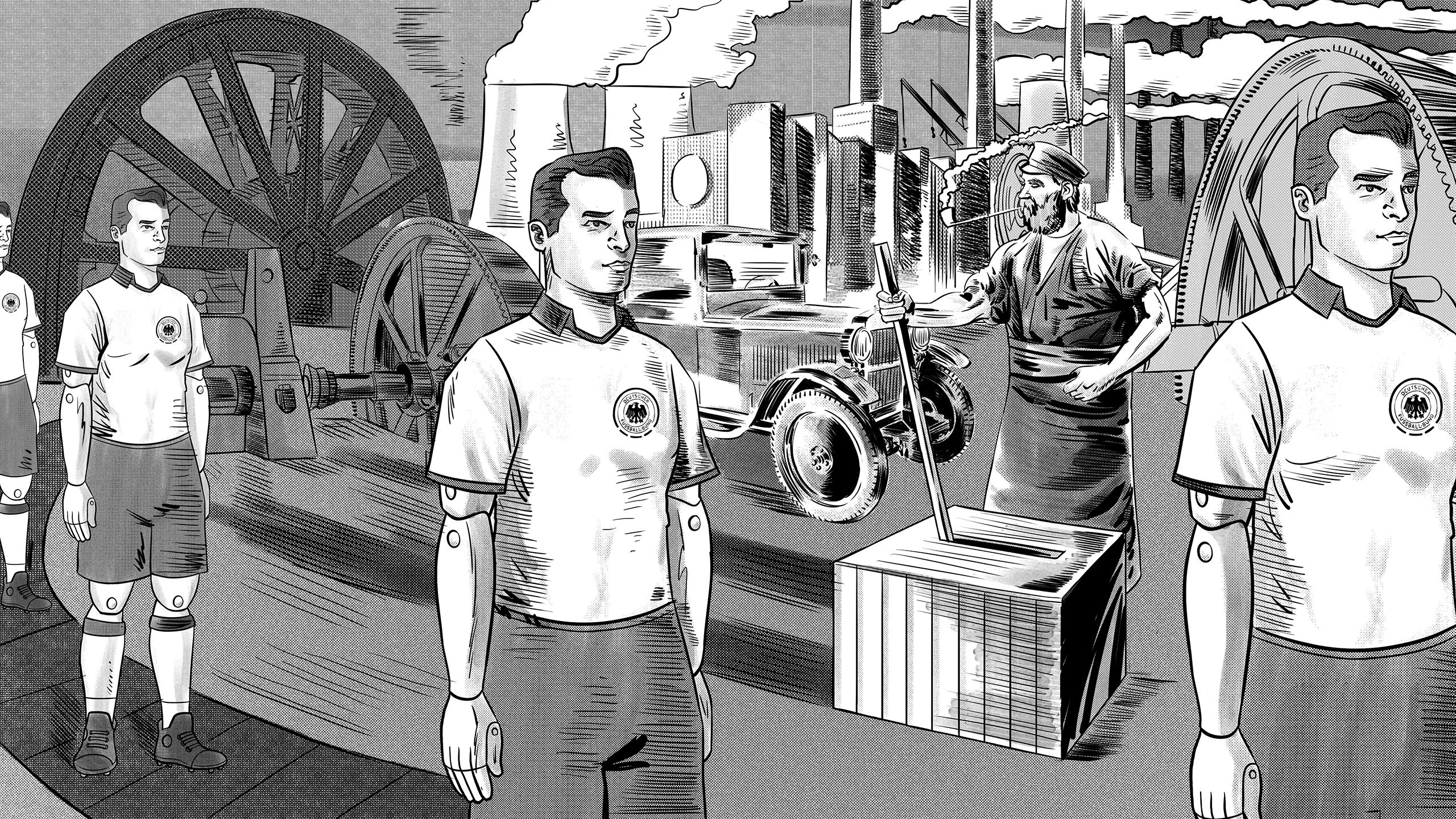

Kramer came through Leverkusen’s Kurtekotten, a state-of-the-art training facility which became the norm for football clubs in Germany following their disastrous Euro 2000 campaign. The German football association (DFB) made it

mandatory for clubs in the top two tiers to run youth academies, and offered financial incentives to encourage clubs to further invest.

Soon, other youth academies in Germany began to catch up to the high standards Schalke had set with their production of youth talent, integrating education into their development by partnering with a local school. Under the guidance

of Bodo Menze, they had fostered the perfect breeding ground for young players, which the rest of the country quickly caught up on thanks to the intervention of the DFB and DFL (German football league).

“In 2001, because of the Euros in 2000 where German football was shattered and laying on the ground with a defeat against Portugal, the DFB and the DFL thought it was time to change a lot in the academies,” Menze told Goal.

“I had the feeling that our way served as an example for them. The co-operation with school which was the central point of all this showed us the way and we showed the way to the league, to DFB and DFL. This meant that we were not changed too much by the DFB because we had already gone that way. In 2001, the obligation of having an academy for the big clubs formed a very good basis for the good results in 2014 in Brazil.”

A 2011 Bundesliga report indicated that in the decade following the change in approach, teams had spent around €500 million (£435m / $585m) on developing and improving their youth players. In addition, the DFB themselves increased their spending in underage football to €9.5m (£8.3m / $11.2m) per year, setting up more than 350 youth centres to facilitate for at least 25,000 young footballers.

By 2012, over 50 per cent of Bundesliga players were academy graduates, in 2013, the Champions League final was contested by two Bundesliga sides and by 2014, Germany were world champions again.

Bayern Munich forward Thomas Muller was on the winning side in both those games, having been not only one of the 50%, but one of the even more impressive 20% of Bundesliga players who came through their own club’s academy system.

Muller is a product of Bayern Munich’s youth academy, having arrived at the club in 2000 just before the DFB and DFL changes began to take shape throughout the country. From the age of 10, he progressed through the youth ranks, eventually making his senior debut in 2008 when he came on as a substitute for Miroslav Klose.

Now the coach of the national side’s Under-17 panel, Klose was a player who always seemed to raise their game when lining out for Germany. He scored twice at the 2014 World Cup to take his overall tally to 16 in the competition, making him the all-time top goalscorer in the tournament’s history.

Klose typified the winning mentality of the Germany team, which often produces performances greater than the sum of their parts. He played at four World Cups, reaching at least the semi-final in each one, helping guide younger players with his vast international experience.

“Every generation brings out its own leaders and special players,” former Germany forward and head coach Jurgen Klinsmann told Goal. “I had the pleasure in 2006 to coach a team led by experienced players such as Michael Ballack, Jens Lehmann, Oliver Kahn and Miroslav Klose.

“Today the German team is led, for example, by Manuel Neuer, Toni Kroos, Thomas Muller and Mesut Ozil. Every generation has its own challenges and dynamic. The chemistry within a team is the most important piece of the puzzle.”

Muller will captain Germany at the 2018 World Cup, and like the player he replaced on his Bayern Munich debut, is expected to pick up the goalscoring mantle and help lead Low’s side to a second successive title. His influence will be just as important off the pitch as it will be on it, building the winning mentality to help bring the best out of his team-mates.

“Every player knows that he’s just one part of the puzzle,” Low told reporters as the tournament approached. “Nobody can become a world champion on their own.”

The construction of this puzzle is a lengthy process, begun when the players enter the youth academies of their respective clubs. The production lines of the Bundesliga teams provide the perfect preparation for the players, delivering a well-rounded education that allows them to become better footballers who can meet the high standards expected of them.

Three-time German Footballer of the Year Michael Ballack is aware of the expectations on Low’s squad to repeat the feat of winning the World Cup, but believes that despite changes in the squad, new leaders will emerge capable of handling the pressure during the tournament.

“I think we have a good chance, like we always do,” Ballack told Goal. “We are the defending champions. I think we have lost a lot of important players over the last four years ,of course, some leaders, but we still have enough quality in the squad to, firstly, replace them but also to deliver, to handle the pressure, and that’s why the balance is good in the team. We have an experienced coach.

“It may be a little bit different if we get to a semi or a final with the expectation because we are the defending champions so we will always have to handle that role. It is a little bit new. But still there are always expectations with Germany. They are what they are, always. The team is prepared for that.”

Ballack cites the winning mentality that is instilled in the current batch of Germany internationals, believing that the years of preparation and organisation could be what brings success to Germany rather than some of their more technically-talented opponents in Russia.

“German mentality in general is very organised. When you do your homework, it doesn’t matter what quality you have, if you do your homework, you are well prepared, you know and you have a certain type of confidence when you go into a game and that gives you a bit of safety,” he continued.

“I think with all the excitement and nervousness that every team and all players have, when you go into big tournaments you have a bit of a safety net because of your mentality because when you look to your teammate you know he is prepared, you know how hard he works and how disciplined he is. And there’s always a little bit extra belief and safety when you go into a match.

“This maybe gives us a little bit extra that in tight situations gives us a little bit of an advantage. It’s difficult to explain. It’s our mentality. Of course we have this great record in big tournaments and to do so you have to have quality and you have to do your homework and I think that’s a good combination we have.”

Germany will have the perfect blend of experience and youth in Russia, with some of last year’s Confederations Cup winners joining 2014’s World Cup winners in a balanced and exciting squad. All have tasted success at club level or international level and know what it takes to become a champion.

It is this mindset that marks Germany out as likely repeat winners of the World Cup. Their players not only raise their game for their country, but battle through the pain barrier to prove themselves worthy of competing for Die Mannschaft.

Manuel Neuer has not played for Bayern Munich since September, but will be Germany’s number one in Russia. He is not just the world’s best goalkeeper on the pitch, but also in his mind too. Other players might have conceded their battle for fitness and watched from home, but Neuer’s determination and presence pushes him further than most others.

“His experience, his personality, his own Manuel-being, is something which caused Jogi Low to keep him in the squad and to give him the chance to be the number one,” Menze said. “He goes with the number one and I hope he will come back with the number one from Russia."

When players join the Germany panel, they put their clubs behind them. The German team is a unified unit, rather than just a collection of club players. As a result, Arsenal’s Mesut Ozil will put a relatively poor season behind him and be expected to shine.

"Ozil has been an excellent talent and is an excellent player today,” Menze continued. “If he has a good day and is in good form, he can make the difference with his left foot in attack."

Neuer and Ozil came through the youth ranks at Schalke, having been shaped into world-class talents in the Bundesliga’s state-of-the-art academies. This is the case for all of the squad, with the likes of Muller and Mats Hummels developed at Bayern Munich.

Germany’s industry has moved on a lot in 100 years, with coal and steel production not as important as it once was. However, their mining of high-quality exportable goods still continues through the youth academies of German clubs, and few would bet against them manufacturing gold once again this summer.

Illustration by Maarten Claassen

maartenclaassen.nl