For Sean Brown, it was a big week regardless.

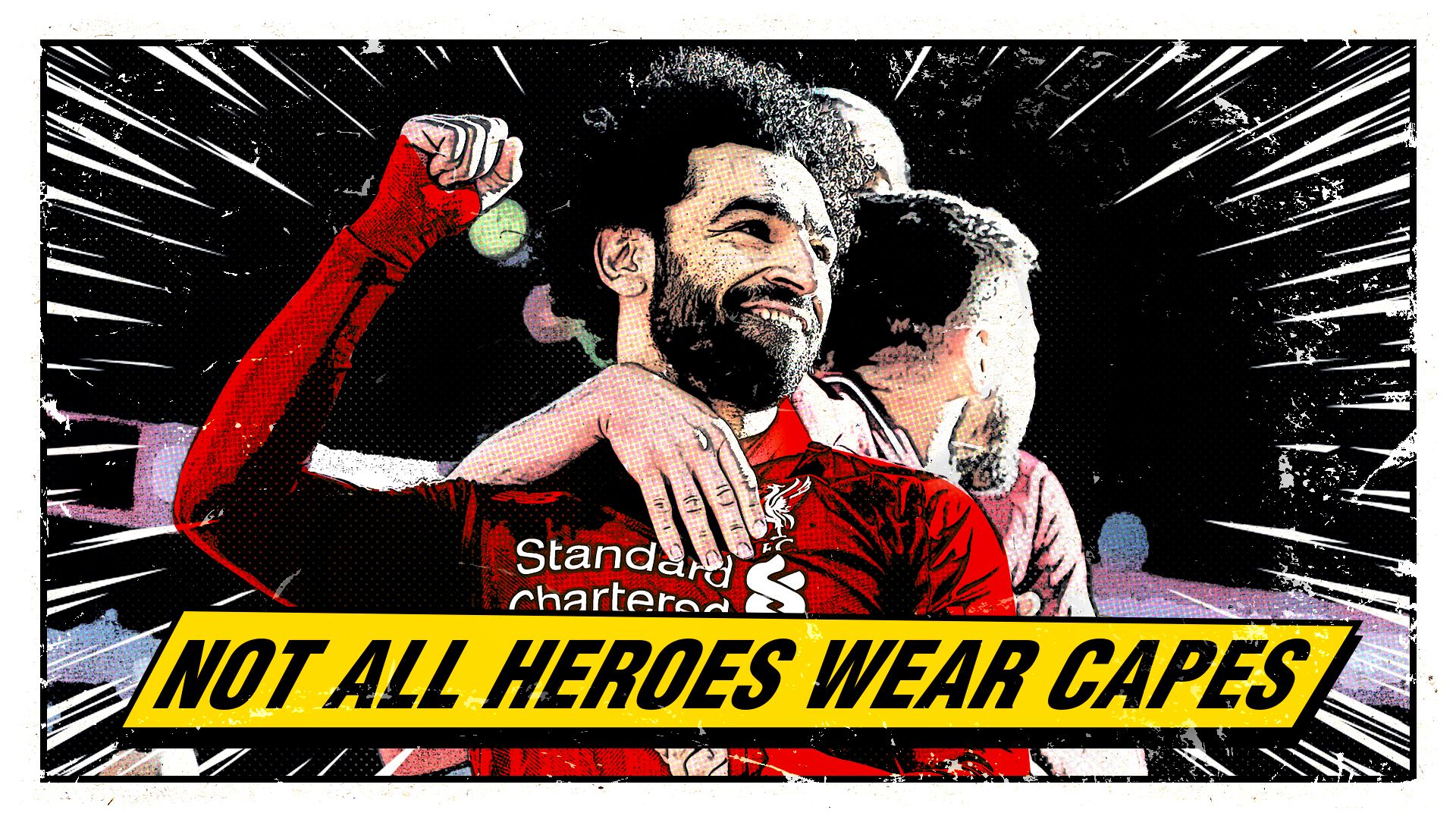

Mohamed Salah made it one that he and his family would never forget. Try telling this lifelong Liverpool supporter that the Reds’ Egyptian King is anything less than royalty.

Sean’s daughter Lucy is 13 years old and has the kind of luck no human deserves. At just six months, she was left severely disabled after contracting a viral infection. Now, she suffers from cerebral palsy as well as epilepsy, leaving her with serious developmental delays. Eight years ago, she required a bone marrow transplant after being diagnosed with Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. Put simply; if courage was currency, Lucy would be the richest person in the world.

In May, as Liverpool were preparing for the Champions League final, Sean posted a video of Lucy on Twitter. It showed his daughter, sat in her wheelchair and oblivious to the camera, singing away to herself.

“Mo Salah, Mo Salah, Mo Salah, running down the wing. Salah, Salah, Salah, la-ah-ah, the Egyptian King.”

A wave of responses followed, with Reds legend Robbie Fowler among those to reply. The Tweet received more than 2,000 likes, the video watched more than 50,000 times.

One of those viewers was Salah himself.

“I was told it was through Danny Ings,” says Sean. “Danny does a lot of work with disabled children and charities, and he’d seen the video, showed it to Salah and the squad.”

Salah’s response, according to one Melwood source, was “right, what can we do for her?”

Swiftly, a shirt was signed and delivered to the Browns’ home in Dingle, just south of the city centre. A small gesture to some, but huge to a family of die-hard Reds. Never to be forgotten.

“I put it on her, took a picture, and she wouldn’t take it off,” Sean smiles. “I had to prise it off her!

“People may say it’s a small gesture, but to me it’s not – it’s huge. So many people talk about footballers and the salaries they earn, that they’ve lost touch with the fans and all that. But to me, what Salah did shows what sort of human being he is. To take the time to have a look at the video, then to send a shirt over, it’s class.

“And there are many other things he does that go unnoticed, too. To me, he’s a genuine guy who cares about supporters and realises how passionate they are.

“Now Lucy knows exactly who Mo Salah is, so whenever she sees a picture of him she will shout ‘Dad, Dad! Mo Salah!’. She recognises who he is and knows his face. And when I’m at the match and the song starts up, it always makes me smile that little bit more. I won’t have a word against the lad.”

Salah’s impact on the field at Liverpool has been remarkable. Since arriving from Roma in the summer of 2017, records have tumbled almost weekly. His debut campaign on Merseyside brought 44 goals, many of them memorable. His first 50 goals arrived in just 65 games – 12 games quicker than any other player in the club’s storied history.

Those exploits are, of course, well documented. What is less known is the effect this humble, softly-spoken 26-year-old from the Egyptian village of Nagrig is having on his adopted home.

Stories such as Sean Brown’s are moving, but not uncommon. When Salah heard, for example, that a gig had been organised in aid of Sean Cox, the Liverpool fan left fighting for his life after being attacked by Roma supporters before the Champions League semi-final in April, he dispatched a signed shirt to the organisers. It fetched £1,400 for Cox’s family. Salah shirts, Reds staff have noted, tend to be more in demand than others, and the man himself is proactive in finding ways to respond to the many requests that come his way.

Liverpool is a club which makes heroes of its players, and in Salah they have one to be truly proud of.

Around three miles south of Anfield, in the heart of Liverpool city centre, a group of supporters gather, cameras at the ready. Selfie time. Selfie time with Salah.

This is Basnett Street, where in May a local street artist by the name of Guy McKinley was commissioned to paint a six metre by three metre ‘Ode to Mo’ mural.

Under the banner The Golden Smile of the Nile, it depicts a smiling Salah alongside lines from a poem written by Musa Okwonga.

Liverpool’s Mohamed Salah

The Muslim maestro

Cairo’s hero

The golden smile of the Nile

The world’s swiftest Egyptian

Blink…you’ll miss him

His scoring rate is one a game

So once a match

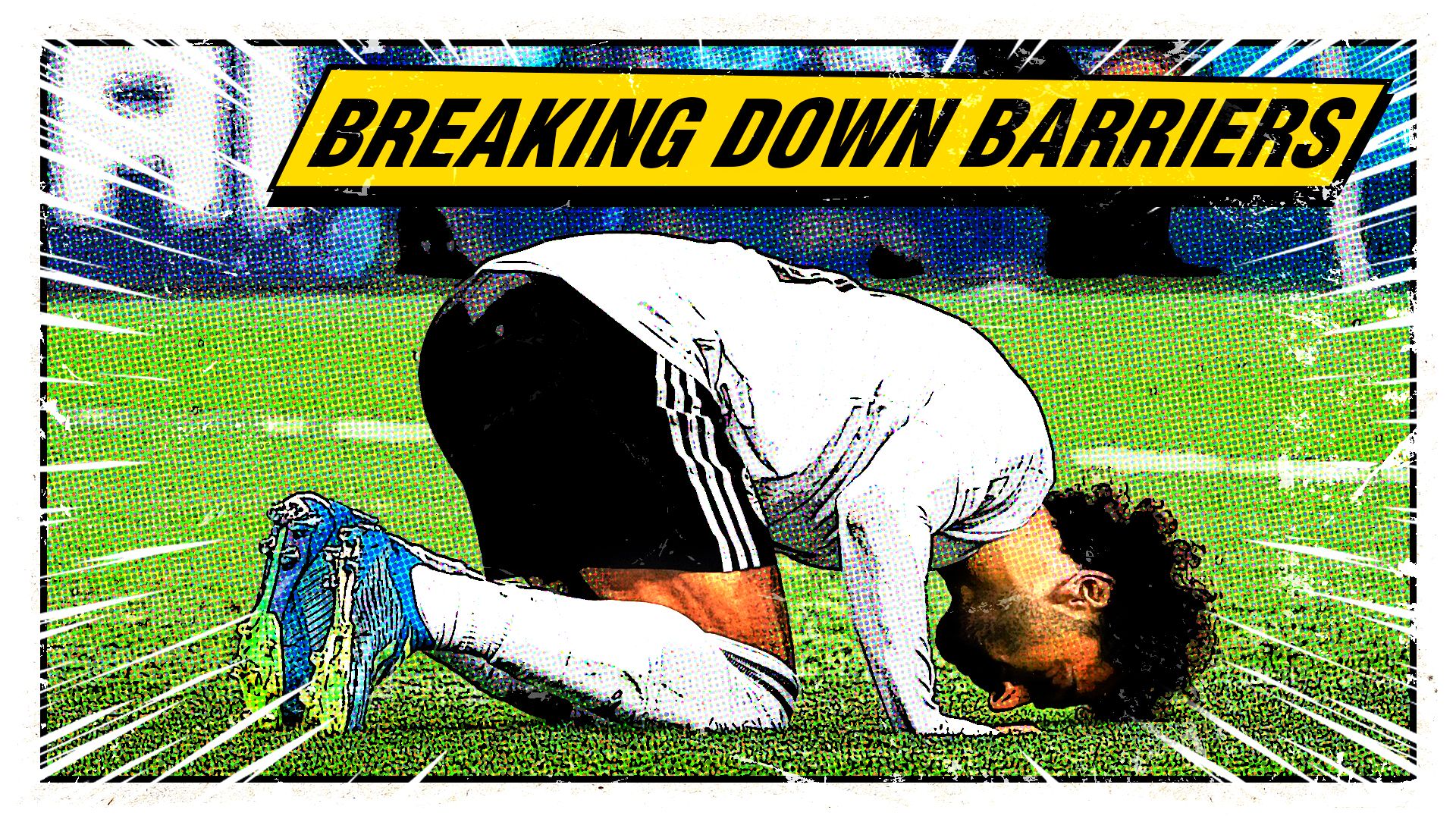

Anfield becomes his prayer mat

It’s a remarkable tribute considering this is a man who has been on Merseyside for little more than a year. Steven Gerrard never got this treatment, nor Jamie Carragher.

Fowler’s face, Ian Rush’s, John Barnes’, none of them stared back at shoppers like this.

In July, Salah posted a photo of himself in front of a similar mural, this time in New York’s Times Square. Others exist around the world, including in his Egyptian homeland. His brand, built on humility, decency and goals, has gone global in the past 12 months.

Back in Liverpool, a few miles from Basnett Street, a local under-8s game is in full swing. The crowd is healthy and respectful, the 4G pitch impeccable, the standard of football impressive.

A goal goes in, a beauty too. Its scorer, delighted, takes off towards the corner flag. Pile-on? Not this time. The youngster sinks to his knees, mimicking the prayer which Salah makes after each goal.

He doesn’t know why Salah does that. Not yet, anyway. “But at some point, one of them will ask,” says the coach, whose own son is playing in the game. “So they’ll learn about his culture, his religion. That’s the kind of impact a footballer can have on a young kid. They can open their eyes to things they’d never otherwise have noticed.”

Religion, of course, is a huge part of Salah’s life. Each week, he and team mate Sadio Mane, another practising Muslim, visit a local Liverpool mosque for Jumu’ah, the Friday prayer. The players mingle and pose for pictures, though their presence now is regarded as normal. Neither Salah nor Mane are the type to court publicity, in any case.

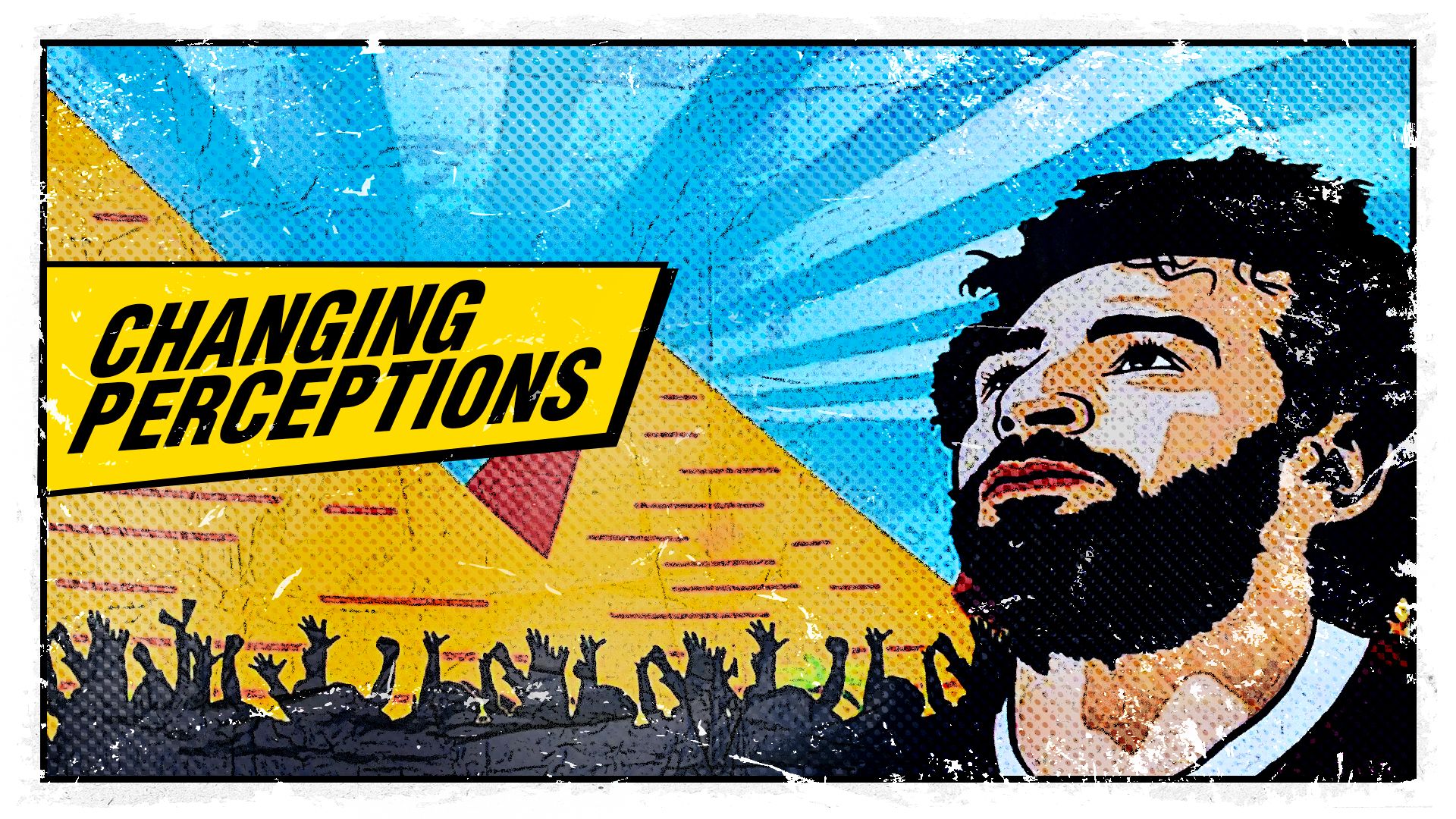

Within the Muslim community and beyond, the hope is that these players, and their achievements on the football field, can help break down barriers with regards to religion, inclusivity and multiculturalism. At a time when Islamophobic agendas are being pushed by the right wing, to the shame of the nation, the exploits of high-profile Muslim sports stars, and the positive image they portray can be viewed as the antidote.

Yunus Lunat is an employment law, sport and equality consultant who has spent time as chairman of the Football Association’s race equality advisory group. And as a Liverpool supporter, he is ideally placed to judge the cultural impact a player like Salah can have.

“In the current climate, the focus on immigration, particularly of Muslims, is huge,” he tells Goal.

“Remember two or three years ago at Anfield and there were two Muslims praying in the stands, and somebody tweeted a photograph saying it was disgusting? Well what do we see now? Salah doing it after scoring and everyone loving it.”

He points to the Multi-Faith Room at Anfield, which is open on matchdays and now sees “an incredible amount of traffic” as evidence of that shifting mentality among supporters.

“What I’m seeing more and more at Anfield are Muslim men and women, comfortable attending and comfortable showing who they are,” he says.

“From anecdotal evidence I know of one of the children I coach, whose mum wears a full face veil and who has been going to games at Anfield. That’s a big thing, for them to have the confidence to do that. I think it speaks volumes, and there’s no question that the way in which the likes of Salah and Mane have conducted themselves, on and off the field, has made a big difference.”

Steve Rotheram, the mayor of Liverpool City Region, has likened Salah’s impact on Merseyside to that of John Barnes in the late-1980s, stating that “his legacy will be much more about what’s happened off the field.”

“To have that breakdown of Islamophobia caused by one person is an absolutely phenomenal achievement," he said. “He has broken down barriers.”

Barnes himself, though, is unconvinced. An intelligent, thoughtful commentator on race, religion and other equality issues, the former Reds winger rails at the suggestion that football can, or should, be responsible for changing attitudes on a national or global scale.

“Look, Mo Salah and Sadio Mane can do nothing about changing perceptions of Muslims,” he tells Goal. “They can change people’s perceptions of superstar Muslims who play for Liverpool, but the average Muslim walking down the street? No.

“It’s the same for me. I couldn’t change the way people thought about the average black person, all I could do was make people accept a superstar black person who played for their team.

“Are people more accepting of black people than they were 30 years ago because I played for Liverpool? No they’re not. But we like this idea when there’s a superstar, that it’s going to change things.

“Look at Obama. Are things changing in America for black people because Obama was president? No they are not. The whole idea is nonsense.

“Until we accept the average black person or the average Muslim as equal, it won’t change.”

Barnes adds: “The problem I have with using football to ‘change perceptions’ is this; what happens if Mo Salah turns out to be bad player? Or Sadio Mane? If they’re good players, then great, but let’s see what people think about him if they don’t score another goal for five years. Will the perception of Muslims change then?

“Idolise footballers for their ability, but don’t expect them to change the world. If you want role models, look to your parents. Don’t look to Paul Gascoigne or John Barnes or Mo Salah and then blame them for what you do.

“As human beings, you have a responsibility. Other people may look at it differently, but I don’t believe footballers, or actors or boxers or singers, should be looked upon to lead the moral compass of the world, and if they don’t then that’s what’s failing our kids.

“Until we change in society, football won’t change. A lot of people think football can change things and that it can beat society. It can’t, society has to be the leader and the driver for change.

“The pressure should be on society to change, not football or footballers. Or actors, singers, rappers, athletes. It’s not up to them to change the world.”

Around a mile from Anfield, on the borders of Kensington, Everton, Fairfield and Tuebrook, sits a placard proudly proclaiming that here lies Britain’s first ever Mosque.

Opened in 1887, the Abdullah Quilliam Mosque was the work of a local solicitor and Methodist preacher, William Henry Quilliam, who converted to Islam following a visit to Morocco at the age of 31, assuming the name Abdullah in the process.

In April 2014, the Abdullah Quilliam was re-opened as a fully functioning mosque after 100 years. Four years later, it opened its doors for another reason entirely.

Football. The World Cup. Egypt. Salah.

The idea came from a local campaign called Fans Supporting Foodbanks, which aims to tackle hunger and poverty issues on Merseyside. Its slogan is ‘Hunger Doesn’t Wear Club Colours’, a neat way to bring together supporters of Liverpool, Everton, Tranmere and beyond. Of late, its focus has broadened; it now seeks to tackle issues of religious and cultural discrimination.

“We realised the power of football, and how we could harness people in the community to come together,” says Ian Byrne, a Liverpool supporter involved with the initiative.

“We had been engaging with local schools, and of course not far from Anfield is the Abdullah Quilliam mosque, so it seemed a natural thing to try and involve them, to break down those barriers.”

The idea, Byrne says, was initially to host a foodbank collection at the mosque. But in June, it was arranged that the doors of the Abdullah Quilliam would be left open, with fans of all faith, colour and background encouraged to bring food donations and then stay to watch the evening’s World Cup matches.

The first game they screened? Egypt versus Russia, with Salah as its star attraction.

“It was a big thing, the excitement around Salah at the World Cup,” Byrne says. “We wanted to use football to demystify the mosque for the local community, to open the doors and let people see.

“Traditionally, you’d go the pub to watch the game wouldn’t you? But that alienates the Muslim community, it excludes them from that community atmosphere of watching football together.

“We know how this world can be. If you listen to the wrong person or read the wrong newspaper, you’ll think that behind the doors of a mosque there’s all sorts going on, things to be suspicious of. It’s not the case, and it was good that we could show that during the World Cup. People could go in and form their own opinion.

“We put the night on, people brought food, we did a massive collection. There were over 120 people there, and half of them hadn’t been to a mosque before. They got a tour, an understanding of the prayers, then we watched the football. It was a wonderful experience, and I know it had a hugely positive impact on a number of people in our community.”

Byrne adds: “It’s in this city’s DNA, that diversity. We are a melting pot and always have been, so it’s hugely important that we continue to do what we can. Using football as a tool for community integration really does work.

“People can be lazy and listen to the incessant drip, drip, drip of some of the right wingers, and that division and distrust that they promote. Our aim is to show that society is about solidarity, it’s not about different races, colours, sexual orientations, religions, it’s about people.

“For us, Salah is not a Muslim, he’s our No.11. But what he’s done is draw attention to it all. To have one of the best players in the world doing his stuff, and representing the Muslim faith, it makes a massive difference.

“I know it gave the Muslim community a lot of pride. It shows their religion in a positive light, as opposed to the way certain other places would like to.”

It is estimated that there are around 25,000 Muslims living in Liverpool, and in the run-up to the Champions League final in May it was reported that attendance at the city’s mosques, particularly among young people, had risen to record levels. In a football-mad city, that should come as little surprise.

“It is down, in large part, to Salah,” says Galib Khan, chairman of the Abdullah Qulliam mosque.

“We are all proud of him. It brings fun to our lives. It brings positive images of everything that is in Islam to games and in people. I think Mo has given us a gift that we will not forget.”

What, then, for the future? Will Barnes’ fear, that widespread ‘acceptance’ of Muslim figures is dependent on their success on the football field, be realised?

Or can the likes of Salah genuinely prompt a change in attitudes in a world where tolerance, patience and empathy is in increasingly short supply?

Yunus Lunat believes they can, though he has urged clubs – and in particularly Liverpool – to take the lead in helping tackle issues such as Islamophobia.

“Football is comfortable tackling racism and homophobia, but I haven’t seen many clubs encouraging Muslim players to stand up against Islamophobia,” he says. “We have Kick it Out, Rainbow Laces, and for me the next barrier, if you like, is to do with Islamophobia.

“With the current climate, having high profile people support such campaigns would go a long way towards supporting those.

“When a player is photographed in a mosque, the publicity goes viral. And sometimes I think clubs are frightened of endorsing that, or of associating themselves with religious issues.

“I think it’s a fear of wider society, and opening up the box to potential issues among other supporters. We saw it with black players in the 70s and 80s, when not many people took that brave step.

“I have worked closely with groups like Kick It Out when I was at the FA, and we have had conversations. But ultimately, there needs to be that endorsement from clubs, and their employees partaking.”

He finishes with an idea.

“I’ve suggested that Liverpool do something on their TV channel about ethnic minority support for the club,” he says.

“I’ve even offered to help them with it, maybe even a monthly slot.

“It’s a perfect story to tell, the history of it, the growth of it and the future of it. That will start not necessarily with Muslims, but maybe with [Asian] supporters or Irish supporters or Americans, and now the Muslim community. That’s a great story to portray.”

One suspects that if Yunus’ idea is brought to life in the future, then a certain Mohamed Salah will feature prominently within it.

It is not just on the fields of Anfield Road that Liverpool’s Egyptian King has made his presence felt.