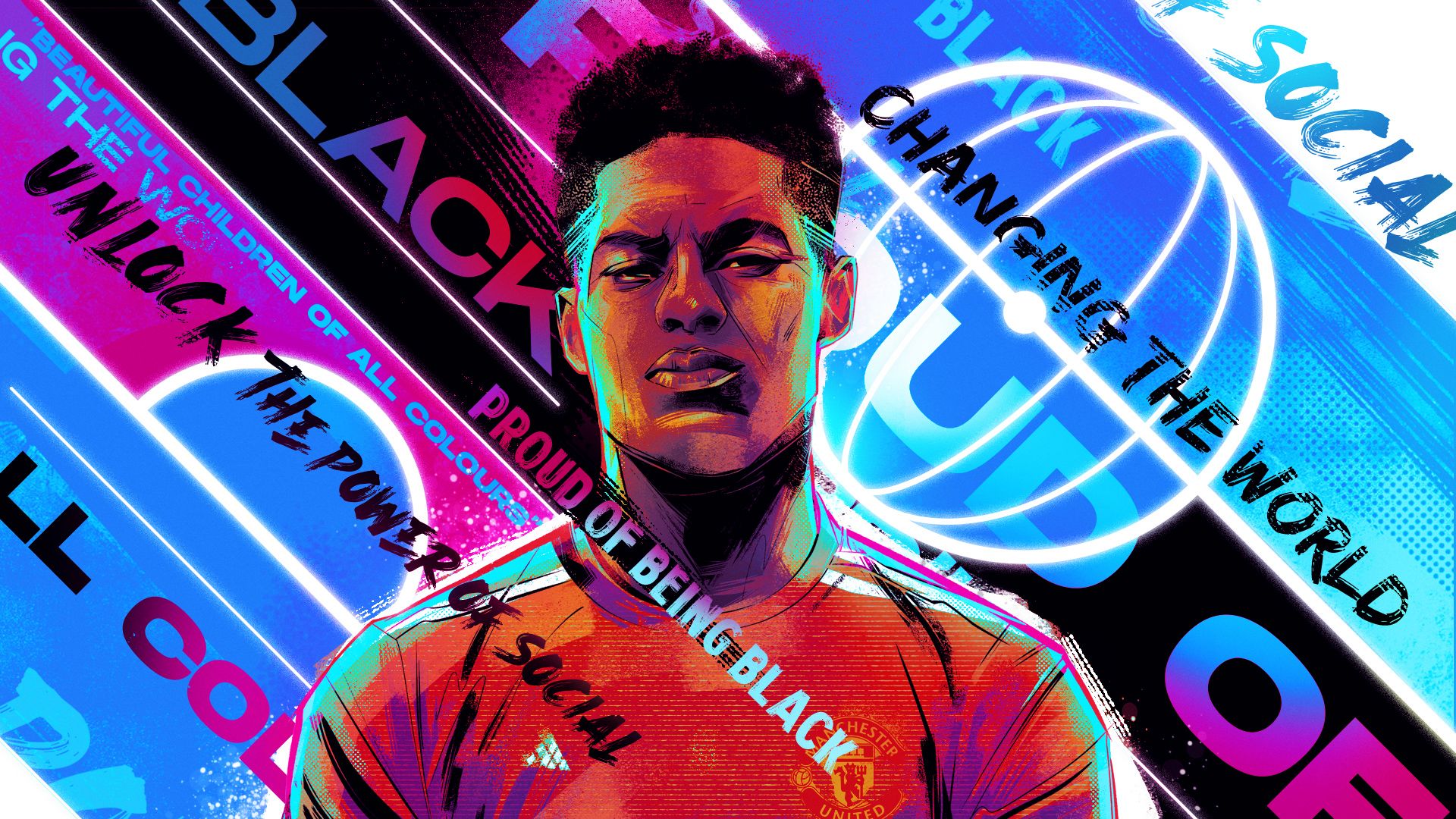

Can Marcus Rashford change the world? The power & poison of social media

By Cady Siregar

The most high-profile opponent to Boris Johnson’s Conservative government in the past year has not been Sir Keir Starmer, the leader of the Labour Party. It has been a Manchester United striker.

Some footballers use their social media accounts to promote commercial campaigns or brag about their latest car. Marcus Rashford uses his Twitter account to confront the United Kingdom's government about its dismal handling of a growing child poverty crisis.

A YouGov poll in May discovered that 2.4 million children (17 per cent) were living in households that needed supplemental food supplies. Later, in December, Unicef launched an initiative to help feed UK schoolchildren for the first time in their 70-year history due to the government’s inability to help those in need.

Labour’s deputy leader, Angela Rayner, said: “The fact that Unicef is having to step in to feed our country’s hungry children is a disgrace and [Prime Minister] Boris Johnson and [Chancellor of the Exchequer] Rishi Sunak should be ashamed.”

At 23, Rashford has become the first footballer to publicly challenge the government – beginning with an open letter calling for a continuation of free school meals during the non-term time – and using his Twitter account to spotlight local businesses helping the disadvantaged across the country.

Some days, he will post for hours on end, relentlessly sharing and retweeting local individuals and councils who are issuing food vouchers, food donations and care packages from city to city.

Sometimes, he will even signal-boost on mornings before he is due to play a match for Manchester United, issuing an apology for taking a break because he needs to prepare for the game.

In doing so, Rashford has unlocked the power of using social media for the greater good. His actions are admirable and inspirational; he has become a true role model, on and off the pitch.

Footballers are some of the most handsomely paid figures in the world of sport, their influence reaching millions of adoring fans worldwide, but so few have used their status of celebrity for the betterment of society like Rashford.

There are those who regularly donate to charity, who have created foundations in their own name and kneel before the whistle to raise awareness in the fight against racism. But Rashford’s direct, public activism – which led to a reversal of the decision not to provide free school meals throughout the holidays – is visible.

Rashford has been awarded an MBE, named the BBC Sports Personality of the Year and listed as one of Time magazine’s 100 Next list. He has also signed with Roc Nation Sports, who don’t choose their clients hastily.

However, Rashford might well state that the true reward for his actions is showing how easy it is to use a platform to advocate for a better future.

Footballers now realise that they possess the ability to impact lasting societal change online. Rashford’s status as a celebrity, and his transparency in openly confronting the government via Twitter, was crucial.

The key component of Twitter is that it eliminates the distance between audience and celebrity.

Rashford’s fight for school meals would probably not have had the same impact, or outcome, if conducted in private.

It is far too easy to dismiss challenges done under discretion – not to mention when conducted by those of lesser celebrity. But Rashford advocated in public – with full disclosure through his public tweets – and it worked. The government buckled under social and public pressure.

The eradication of the gap between the celebrity and the public, however, also poses danger.

For every positive way that Rashford has used Twitter to fight for social change, the same platform has been failing him.

Social media can be every bit as harmful as it can be powerful. Even Rashford is not protected from the cruelty of cyberspace. He is not immune to the toxic side, targeted with racist abuse on the same website he used to advocate for free school meals.

The same dynamic that allowed Rashford’s online campaigning to be so effective works for people who want to abuse others. Any kind of illusion of distance has vanished.

Rashford was subjected to online vitriol following Man Utd’s draw at Arsenal in January, describing the incident as “humanity and social media at its worst”. The same week, fellow Black athletes Reece James, Romaine Sawyers, Axel Tuanzebe and Anthony Martial were also met with abuse.

Rashford, to his credit, did not want to give the racists an elevated platform by engaging them in their hate, saying: “It would be irresponsible to do so … I have beautiful children of all colours following me and they don’t need to read it.

“Yes, I’m a Black man and I live every day proud that I am. No one, or no one comment, is going to make me feel any different. So, sorry if you were looking for a strong reaction, you’re just simply not going to get it here.”

Rashford is right. He has also challenged social media companies to better handle instances of discrimination and bullying online – something which should have started much earlier.

Bullying on social media happens because those who do it want to embarrass their victims. There is a sadistic glee that comes with telling people how ridiculous their mistakes were.

Coupled with mob mentality and the phenomenon of feeling closer to such a powerful figure through Twitter – only an “@” separates you and the most famous people in the world – this increases the problem tenfold.

Racism within football is a deep, long-standing problem, but internalised racism and bigotry is embedded in every aspect of society. Unless systemic racism is addressed in a more direct manner from the ground up, no meaningful change will come.

Rashford and other footballers are far from the only victims of online abuse. Cyber-bullying takes place across the whole website towards the everyday, non-celebrity Twitter user.

The wider discussion is about how to better protect their more visible users – Rashford’s case gets particular attention because he is famous – but social media companies can still take steps to tackle this sort of harmful online abuse more readily.

Both Twitter and Facebook have the responsibility to regulate this sort of behaviour,

The Professional Footballers' Association (PFA) has asked for platforms to immediately disallow users from using explicitly racist terms and emojis, stating that they are responsible for such abuse taking place on their website.

Twitter has taken positive steps in allowing certain users the option of only letting people who follow them reply to their tweets. This could be expanded so that certain figures have the choice to not be tweeted at by non-verified users.

The platform must also immediately ban users found to be spewing racist abuse.

“There is a greater calling than profits, and Mr Zuckerberg and Twitter’s CEO, Jack Dorsey, must play a fundamental role in restoring truth and decency to our democracy and democracies around the world,” wrote Greg Bensinger, a member of the editorial board of the New York Times.

“That can involve more direct, human moderation of high-profile accounts; more prominent warning labels; software that can delay posts so that they can be reviewed before going out to the masses, especially during moments of high tension.”

There have also been calls to abolish anonymity on Twitter, the argument being that racists hide behind the safety of an anonymous account so their real identities cannot be traced.

However, removing anonymity is not the answer. For some, the website is an online safe space where they can share their views and details of their lives that they would be punished for in the real world.

For those who identify as LGBTQ+, but who cannot live their life freely due to societal pressures and regulations, they can find a home in an online community. To expose those individuals would only cause harm.

Requiring full identification to use a social media website will not prevent racist abuse either. Facebook requires users to sign up with their legal name and a form of ID, but that does not stop hate speech and harmful conspiracy theories with offline consequences.

What Mark Zuckerberg thought he had created so innocuously from his Harvard dorm room has morphed into a powerful cyber-weapon that not only spreads abuse. It also has the ability to influence the outcome of elections and has been used to incite real-world violence.

Facebook, initially conceived as ‘Facemash’, was designed by Zuckerberg as a means for his college friends to rank his female classmates by order of physical appearance. He expanded on the idea, creating a virtual social network for college-aged students that quickly morphed into something far more substantial. It provided a platform for global connection.

But it has also brought along the power to influence certain views, something made all the easier through personalised timelines and targeted ads.

Facebook has created a domino effect in our society, with misinformation and disinformation influencing presidential elections in the United States.

It goes beyond that. The Mynamar military infamously used Facebook to escalate hate speech regarding the country’s Rohingya Muslim population leading up to 2017, which led to mass murder and genocide.

Social media incubates hateful rhetoric, but it is a reflection of our society; these views will continue to exist once these users log off from the internet.

People still shout racist slurs at stadiums where their name and seat number are stored by the club, when they are knowingly broadcast on camera. Some just do not care about consequences.

Rashford has not specified what kind of accountability racists deserve – be it a form of punishment, or education, or both. Twitter must take greater measures to suspend, ban and delete accounts quickly to protect their users more effectively. The responsibility of trying to better society shouldn’t rest on Rashford’s shoulders, and we won’t make progress if these issues are not addressed at a systemic level.

But if a 23-year-old can challenge the government to feed children in need while still combating racial abuse, it should not be too big of an ask to have a website to take on stricter and clearer safety measures, with the ultimate goal of discouraging such visibly toxic behaviour.

Rashford is one of millions everyday targeted with online hatred, but being vocal on the issue will hopefully shine a light on an issue that happens far too often and freely on an internet platform we all collectively think of as our home away from reality – a place we should consider to be safe.

And he does all of this – holding the UK government accountable and calling out bigotry – while still constantly turning out solid performances as a Manchester United and England player.

So, can Marcus Rashford change the world?

He already has.

Illustrations by César Moreno