But there are other stories, quieter ones, that exist on the margins of the great tales. Episodes that seem minor but end up illuminating a tournament, a country, or an entire generation from an unexpected angle.

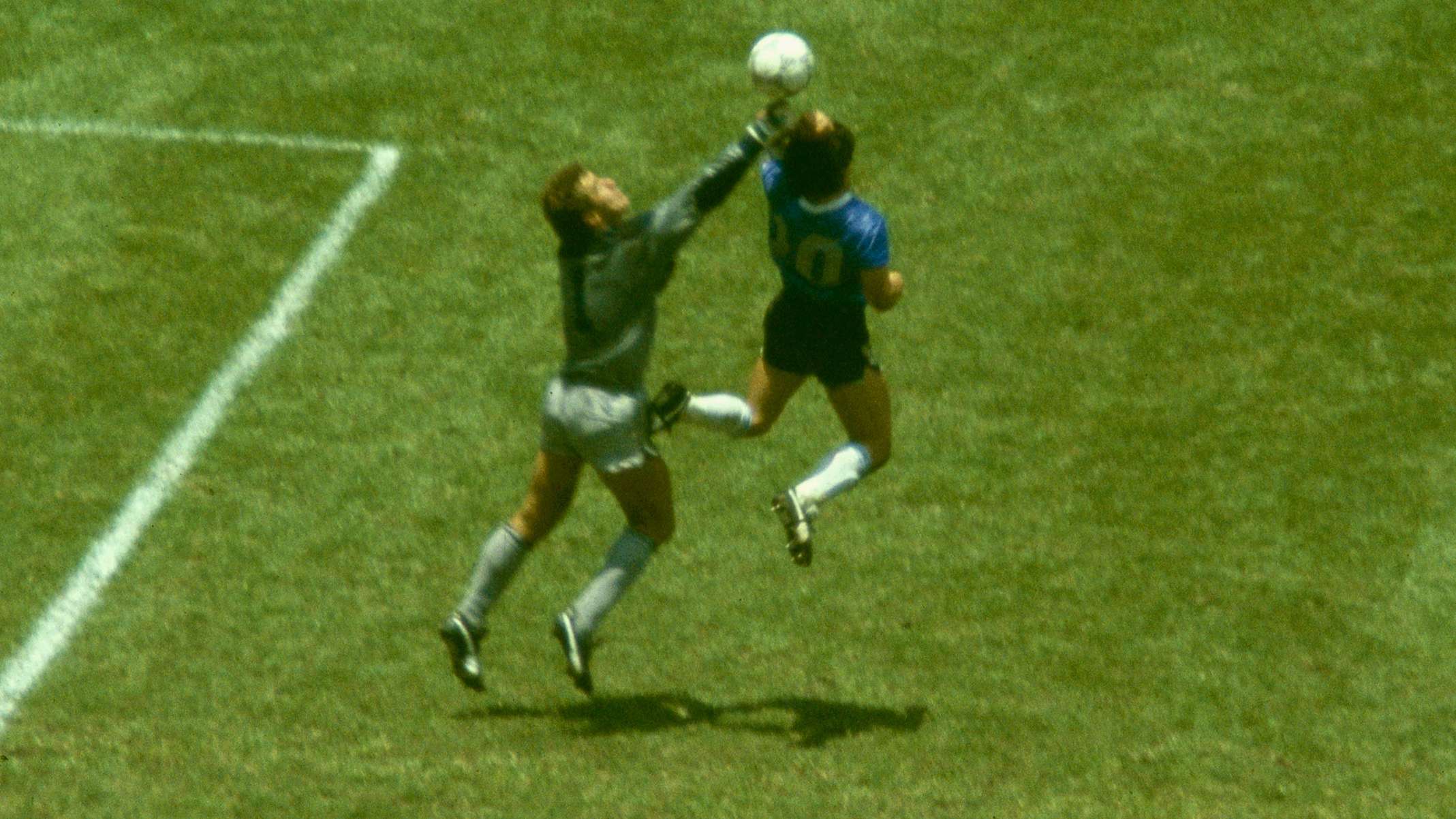

Mexico ‘86 was full of such moments; the midday heat of Mexico City, the altitude that forced Carlos Bilardo to plan obsessive training sessions, the press conferences where Maradona answered incredulous journalists with sharp, unforgettable lines.

And among those parallel stories is one of the most colorful: that of the ‘fake’ jerseys Argentina wore in their quarter-final win over England - acquired at the very last minute in Tepito, the roughest neighborhood in Mexico City.

This is the first story in GOAL's new World Cup series, Icons. Listen to the podcast version on SPOTIFY or APPLE now.