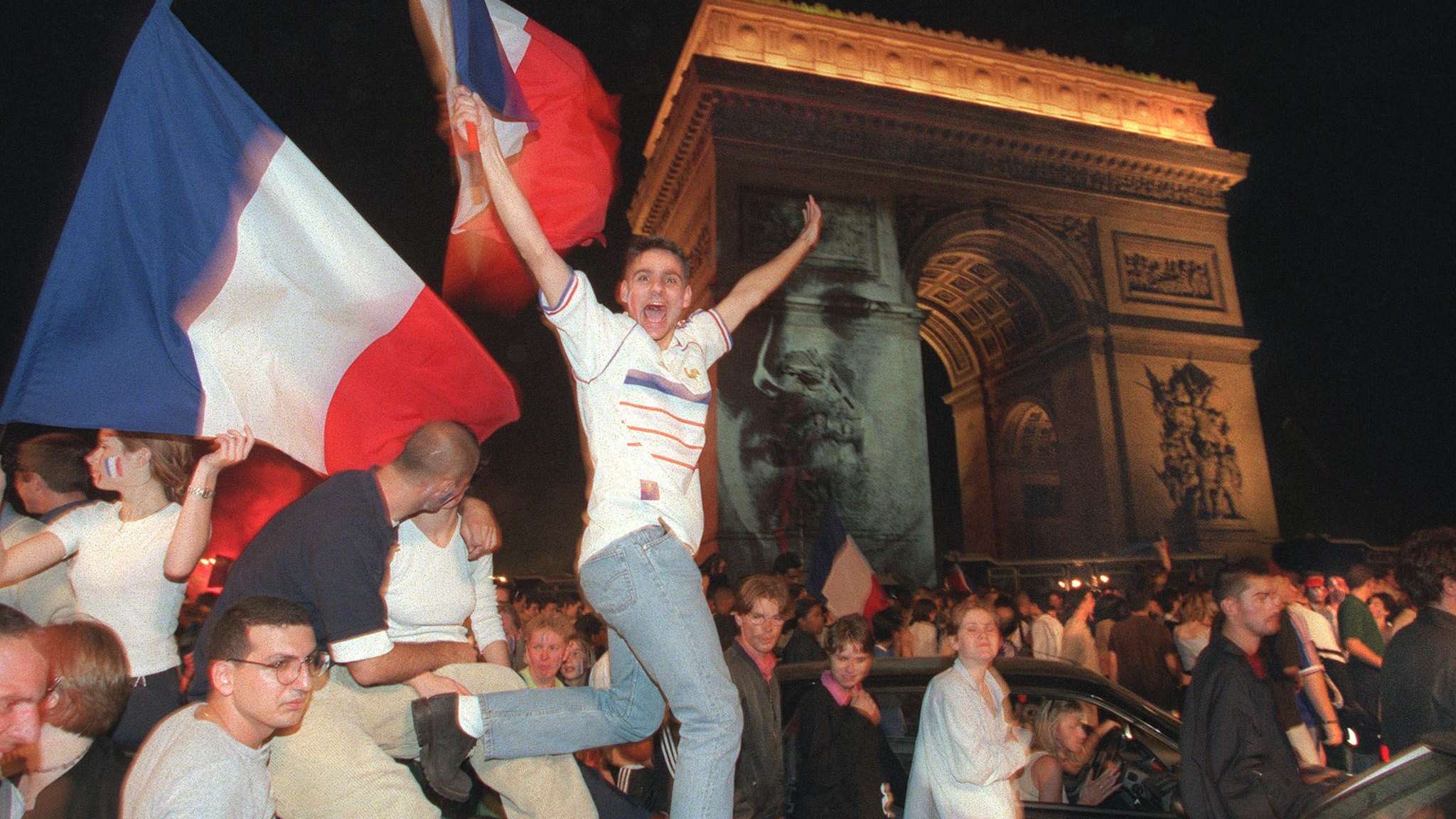

On July 12, 1998, France won far more than a trophy. They shattered a historical complex and forged a legend that endures to this day.

Before that date, French football was haunted by its demons. A founding force behind the world's greatest competitions, France embodied a cruel paradox: an influential nation that was rarely victorious, an inventor unable to master its own creation. Its identity had been shaped by a culture of ‘glorious defeat’ – that nobility in failure which, over the years, had morphed into a genuine psychological burden. To grasp the seismic impact of 1998, one must understand the depth of the wound it healed, a scar born from three converging traumas.

The first remains etched in the collective memory as the ‘Seville tragedy’ of 1982. That World Cup semi-final against West Germany stands as a painful legend. Harald Schumacher's assault on Patrick Battiston – leaving him unconscious with broken teeth and damaged vertebrae – was a flagrant injustice that went unpunished. The penalty shootout defeat, after leading 3-1 in an epic period of extra-time, forged the image within France of the ‘magnificent loser’. France's ‘magic square’ of Michel Platini, Alain Giresse, Jean Tigana and Luis Fernandez produced the most beautiful football in the world, yet seemed too romantic, too fragile to triumph. Seville planted a pernicious notion that glorious defeat was preferable to victory without flair – a national narrative as poetic as it was paralysing.

The second trauma was one of pure humiliation, as the end of Platini's generation ushered in a catastrophic decade. France failed to qualify for Euro '88 or the 1990 World Cup, and were then eliminated without distinction from Euro '92. However, the national team endured its darkest night on November 17, 1993.

That evening at Parc des Princes, a simple draw against Bulgaria would have secured passage to the World Cup in the United States. But in the dying seconds, a devastating counter-attack finished by Emil Kostadinov shattered all hope. Defeat was no longer heroic – it exposed a mental capitulation, a pathetic incompetence. The myth of the ‘magnificent loser’ evaporated, replaced by the ignominious tag of simply being ‘losers’.

Finally, the third trauma was that of a tainted victory. On 26 May, 1993, Marseille had proven that France could win by claiming the nation's first European Cup against the mighty AC Milan. This triumph, which should have served as a catalyst, was immediately corrupted by the VA-OM match-fixing scandal that involved Marseille and Valenciennes. Revelations of the rigged match between the pair led to Marseille being stripped of their domestic title and relegated.

Four pivotal moments thus marked this dark period: Seville 1982; the failure to qualify for the 1990 World Cup; Marseille's tarnished victory in 1993; and the cruel defeat to Bulgaria later that year, which confirmed the French inferiority complex. Hope proved short-lived, leaving a nation without a single moment of pure glory to cling to.

In 1998, then, France wasn't awaiting victory; it craved redemption, liberation from these spectres of the past. It needed an unquestionable triumph to erase the injustice, achieved with mastery to forget the incompetence, and carried by symbols of integrity to wash away the stain.